Past to Present is a series of articles by PCCGB member Roger Bradley. They are a mixture of anecdotes and recent adventures with classic cameras, old processes, pinhole photography and much more.

Musings and considerations about my vintage camera collection during Covid

I really enjoyed the online talks involving cameras at this year’s national AGM, in particular John Wade’s presentation on early digital cameras and John Marriage’s research into the under a £1 new, circular, 127 camera called the Pic. Both talks reinforced my belief that cameras don’t need to be valuable to be interesting and worthy of research time and dare I say it – use. I should also add photography books and photographs whose interest to me often doesn’t correlate with their acquisition cost.

Over the years I’ve helped collectors surviving partners to dispose of camera collections and even rooms full of bits and pieces whose combined value often surprised the recipients. Recently, at the other end of the scale, some impressive collections owned by Club members have been successfully sold through specialist auction houses. During my time as Chairman of the PCCGB, I encouraged and helped to organize important sales of bequests to the Midlands Region. All of the cameras involved were sold to members with the proceeds passing as instructed in the deceased members’ wills, for the enjoyment of their fellow Midlands Region colleagues. This idea has since been replicated nationally, albeit with a huge amount of work for the committee members involved, and the funds gained have certainly helped the club’s balance sheet.

Returning to the present, another common syndrome many of us experience, particularly those of us with limited space, is a desire to start again in another area of collecting cameras or even in a different collecting theme. I’m approaching this decision with some of my cameras that are border line vintage, heavy, and just not being used. I was late to use digital SLR cameras but their advantages have finally won me over. Despite this, our darkroom is still in use and we are quite attracted to pinhole photography and occasionally use our lovely large format cameras, loading them with increasingly expensive film and sometimes photographic paper.

A long preamble – so I’d better identify two cameras I’ve hardly used in the last two years at least. They are my Kiev 88 and Pentacon six, both equipped with TTL view finders. The Kiev 88 was inspired by the Hasselblad 1600F model and uses detachable film magazines. The Pentacon six looks like an overgrown 35mm camera and so each film change takes longer but is actually less of a fiddle to accomplish.

Kiev in the Ukraine has been important to these cameras for many years and two companies there, Hartblei and Arax (both have easily located websites) are involved in camera improvements and repairs. Hartblei also make new products, including the Pentacon Six mount fitted to a version of the Kiev 88 camera allowing a bigger range of lenses to be used.

On an impressive much bigger scale, the company has combined with Carl Zeiss in Germany to manufacture what they call, Superrotators – incorporating sophisticated 360 degree shift & tilt mechanisms in both directions. This high end optical equipment is intended for professional and possibly wealthy amateur users.

I bought my new Kiev 88 camera from Hartblei in 2012 and the TTL finder later. At the time new additional film magazines were still available. My current Pentacon six is virtually brand new and came with an hour long tutorial from the keeper of the excellent Pentacon six.com website about two years ago. I have used earlier examples of this camera to produce some satisfying images, but this one, despite me buying it a waist level finder to reduce its bulk, has just taken its first pictures for me.

Should I sell them both? Of the two, I feel that the Kiev 88 is more useful for studio and technical work due to its magazine system allowing fewer interruptions when taking portraits for instance, but the Pentacon six is lighter and quicker to use otherwise. Both cameras need careful adherence to their instructions to avoid expensive repairs caused by misuse.

I’ve used them both to illustrate this article and perhaps help me to reach a decision. I must admit that even if both cameras departed from my collection, various medium format cameras would remain, particularly my much loved Rolleiflex 3.5F, bought from Ron Holloway and treated to a prism finder a couple of years ago.

(Originally published in Tailboard, Nov 2020)

Mamiya Mania

As will be revealed, this article, has proved to be the most expensive and frustrating of any I ever previously completed for Tailboard. It’s the story of my acquisition of two Mamiya 6 cameras, totally different in design and made about 40 years apart.

I was attracted to the nineties vintage Mamiya 6MF (pictured, above) because of its square format, eye level viewfinder and modest weight compared to all metal cameras. MF stands for multi format, a concept derided by the American reviewer Ken Rockwell. Different formats are achieved by the insertion of masks which need to stay in place for the whole film. Rockwell asserts that most photographers are capable of cropping their images after processing and don’t need these accessories, Mine didn’t come with masks although the viewfinder displays various reminders of them.

This camera was used professionally by my friend, the photojournalist Barry Lewis, whose work is well worth looking up online. I’ve bought several cameras from Barry who always says, “take it away and try it out.” I followed his advice and my first task was to download the camera’s instruction book. This showed me how to use the mechanism which opens and closes a light shield curtain which protects the film when changing lenses. An incentive for me to buy this particular camera was that it came with the superb 50mm wide angle lens in addition to the standard 75mm.

A collapsible lens mount reduces the camera’s bulk when not in use. Like its older namesake, 120 film is used although a 35mm adaptor was produced. Exposure is determined via aperture priority or manually with the correct speed being indicated by a flashing red LED in the viewfinder.

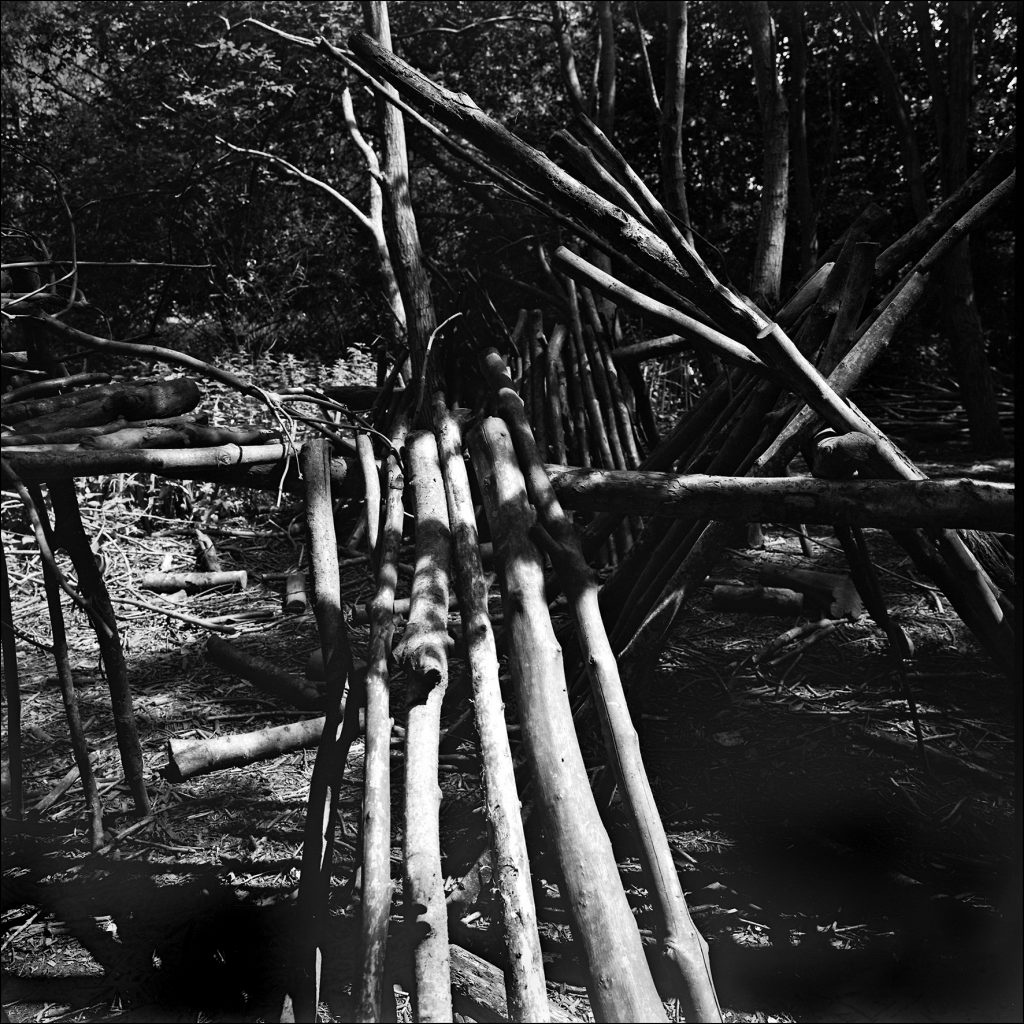

Making a rare trip away from our Covid isolation we visited a park which has a small wood yard for children to choose their materials to construct a den. The light was excellent and I returned home satisfied and was further heartened when my film loaded quite smoothly into the developing tank. All went well with the processing until I poured the stop bath back into its container and was alarmed by the film reel emerging from the tank only to disappear under the work top. I threw myself towards the light switch before spending quite a few minutes looking for the errant reel. After fixing, I was partially relieved that the film wasn’t totally fogged and I chose a frame that seemed to have almost escaped unscathed.

My articles reflect the theme, Past to Present, so I decided to buy an example of the earlier Mamiya-6 enlisting friend and fellow member Andrzej Jablonski with the task of choosing an example in good cosmetic condition on Ebay. This was sourced from Premium Camera Store in Tokyo and arrived in less than a week, followed by a demand for £32 duty plus charges from Fedex who have compounded the issue by claiming I haven’t paid their bill. In this climate people seem to refuse to answer phones or any other form of communication whilst retaining the ability to up their hostile demands or court action will ensue. Fortunately my bank statement can be used in evidence.

Two features on my new camera immediately stood out – The lens is an Olympus D. Zuiko. The ‘D’ stands for 4 elements. Mamiya bought lenses from various companies and even invited customers to provide their own, a far cry from the superb Mamiya-made lenses the new Mamiya 6.

The other feature was the wheel on the rear of the camera which moves the focal plane to focus the picture. Our editor, David, points out that Ensign Commando has a similar arrangement but was there a licensing arrangement between the two companies? YouTube has been useful to identify the exact model of my camera – IVB c1955 – and also provided a demonstration of the film loading procedure. It became apparent that the camera had a few mechanical issues but by trial and error I managed to obtain 10, 6X6cm images. I did contact the company in Tokyo and was told that I could return the camera for a refund. Perhaps unwisely I didn’t, on the grounds that it would mainly be a display camera and that my article deadline was imminent. Unfortunately after processing a film showing the new old people’s home across the road from our house, I discovered that most of the developed negatives were showing a patch of fogging, confirmed by the classic test of looking through the bellows towards a bright light.

An arrangement was made to have the old bellows removed by repairer Miles and a replacement made by Custom Bellows in Birmingham, and posted back to Miles for installation. Just before posting the camera to start this process I set up my Manfrotto tripod in the garden and put the camera in place. Alarmingly, for the first time in at least thirty years I failed to lock the plate onto the tripod correctly and the camera fell onto our garden path (see front cover of this Tailboard). Fortunately, the impact missed the lens but slightly distorted the folding linkage. I asked Miles to assess the damage before going ahead with the new bellows. He seemed quite relaxed about this and he should now have received a quite expensive piece of folded material.

Back in May 1940, Tsunejiro Sugawara and Seichi Mamiya, businessman and engineer respectively, launched their first camera, which in its various forms was in production for 18 years. Later in the 1980s in response to a difficult financial climate

the new Mamiya 6 and 7 were introduced – ground breaking cameras albeit with shorter production lifespans.

I feel pleased to have acquired two important cameras in the history of Mamiya and suspect that they will not be the last Mamiya cameras to join my collection.

A Pair of My Favourite Folders

Some of you might remember my passion for Agfa cameras a few years back. Before I called a halt there were 140 plus Agfa’s lined up in my office. Now I’m down to 10 including the impressive Super Isolette.

Giving a talk sometimes has unexpected results: during a presentation to a local camera club I mentioned my Agfa interest and the result was a telephone call from a member of the audience. His neighbour had offered him an Agfa Super Isolette which he asserted didn’t work and was destined for the rubbish bin. Would I like it? I gratefully accepted this queen of the Agfa’s 1950’s fleet.

I took it to my excellent camera repairer in Stoke on Trent and quickly emerged with a fully working camera and a bill for £3. What a pity he decided to give up repairing cameras to become a plumber.

Agfa made this camera between 1954 and 1957, naming the identical model for the American market, Ansco Super Speedex (see advert, opposite, from 1954). The film winding window was eliminated because the camera was equipped with a mechanical film sensing mechanism which could detect the start of the film by piercing the backing paper.

The excellent, Tessar pattern, 75mm Solinar lens provides 12 6x6cm negatives on 120 film.

From 1960 for 4 years, the Russian KMZ company based in Krasnogorsk, produced their own version of the Super Isolette, called Iskra, or Spark, in two models. The later second type incorporated a selenium cell light meter.

Iskra was the name of an underground newspaper started by Lenin in 1900. I have read claims that you had to be a photojournalist to be allowed to buy this camera. Perhaps this requirement allowed access to the first cameras produced.

Although the design resemblance between the two cameras is obvious there are some differences: the Iskra has strap lugs, is slightly taller and 51 grams heavier than its German inspiration. The lens and shutter specifications are the same.

My Iskra was bought on Ebay from a Russian dealer in Siberia. He warned me that it would take 5 weeks to reach me. It did, and was well packed in Russian newspapers.

Recently I have used these cameras and both seemed to be suffering from focusing stiffness. I suspect they need a service which I plan to arrange soon.

They have the virtue of being easy to carry around in a large pocket, but compared to a modern roll film camera such as the Mamiya 6, they feel awkward and are slower to use.

They are both currently available, with the Agfa camera fetching nearly £500 for a mint example whilst the Iskra is being offered for less than half as much.

The pictures were taken on Fujicolor Superior 400 ISO film using my Agfa Super Isolette (above) and KMZ Iskra camera (below)

Pilot Super Meets Great Wall

A few years ago I started to collect Chinese cameras, particularly TLRs, but soon found that they were very similar in design despite having different names, albeit some exotic, like the Five Goats. Then I noticed the Great Wall Df4 single lens 120 film reflex made by the Beijing Camera Factory and began my search to buy one. This camera was manufactured between 1981-5 in several slightly different variations, during which period tens of thousands are said to have been made.

About 20 years ago, Club member Gerry Walton revealed to me where I could still buy a new example of this camera, which I was able to do, and found the pictures it made quite acceptable. I did what most owners have tried to do with the Df4 – unscrew its 90mm, M39 threaded lens and replace it with another lens. Apart from one enlarger lens, I soon found the lack of clearance prevents you from attaching alternative lenses.

Recently I have read that the removable camera lens allows its owner to use it on an enlarger.

What you can do is attach close up and similar optics to the front of the camera lens which will give you plenty of possibilities.

The rise of the Japanese mini lab, whose importation led to rapid processing of 35mm colour film in China, killed the interest in this roll film camera and thousands were sold off cheaply.

Nearly all descriptions of the Great Wall SLR models mention that they were inspired by the KW Pilot Super produced in the outskirts of Dresden from 1939 to 1941 (this location enabled them to survive the heavy Allied bombing of central Dresden).

Kamera – Werkstätten Guthe & Thorsch had been established in 1919. The story of this company is complex and dramatic and is well worth investigating further.

John Marriage generously loaned me his Pilot 6, a predecessor of the Super model, and I decided to search for the Super model whose main difference is to have a built in extinction light meter. They were not originally imported into Britain but a surprising number are currently for sale in Europe and the USA. Not all have worn well, something that I can identify with, being about the same age as the camera. I bid for a camera based in France only to be defeated in the last ten seconds by an auto electronic bidder. The owner of the camera mentioned that he had a second example of the same model and would list it tomorrow at 1pm. What he didn’t mention was that this alternative was based in Florida and in a different time zone. Somehow I managed to buy yet another Super from The Hobby Shop in Bakersfield, California.

This duly arrived and is in good condition except for a corroded viewing screen which several club colleagues say could be replaced with a donor mirror from a Polaroid SX70 or similar. In the meantime I’ll use the direct vision finder employing the depth of field table.

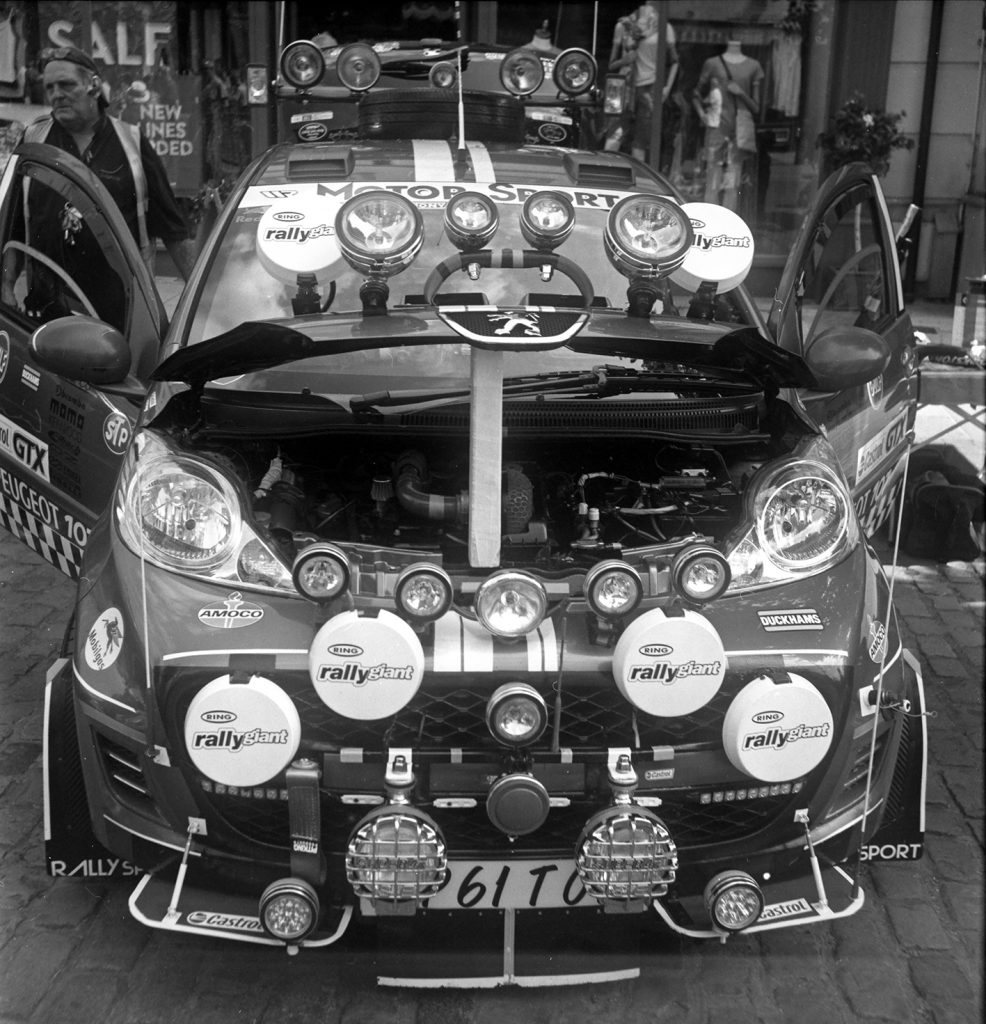

After a couple of false starts with out of date film, including a 1984 vintage HP4, I used the annual Vintage Car Show in central Market Harborough as a chance to get serious with recent FP4 film. I also used the cameras separately to avoid confusion. The viewing was much more effective with the Great Wall but the Pilot Super was slightly smoother in its mechanical operation.

The results were vastly improved from my test shots.

Would I use either camera regularly in preference to a Kiev 88 or Pentacon 6 SLR? Definitely not but as the Antiques Roadshow experts often say, the reward for collecting is the pleasure we receive from owning the items.

A Pilot 6 and Pilot Super(1939-41) flanking their imitator, the Chinese Great Wall Df4 (early 1980s)

Taken with Pilot 6

Taken with Great Wall Df4

Taken with Great Wall Df4

An Unexpected Adventure in Nigeria

Back in 1979 I was managing Lansdowne House Teachers Centre which contained a variety of subject departments supporting the work of Leicestershire teachers. My contribution was a practical resources area which included the design and production of learning materials. A feature of the latter was a strong emphasis on photography, including a teaching darkroom. We had Olympus Trips and Pentax K1000 cameras for loan. Once we held an Olympus Trip “Trip” to Skegness which produced a varied exhibition in the centre.

In the Spring we had an impressive visitor, organized by The British Council. Marian Taylor was head of a centre in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria with similar ambitions and facilities to support teaching staff in her city. Later in the year I received a telephone call from the British Council. The caller’s first question was to establish if I was free for a month during the forthcoming Summer because I had been requested by our earlier visitor. Having accepted her invitation I enquired if it would be acceptable for my then partner, Sally, to accompany me. What followed was an amusing response from my caller along the lines of, “The British Council don’t like this sort of thing but at least you haven’t just turned up with your girlfriend in tow!” I politely offered to withdraw but this wouldn’t have been acceptable to her Nigerian client, so our visit was arranged.

We were booked to fly from Gatwick on a British Caledonian DC10 aircraft. Unfortunately, this type of plane had been grounded due to a safety concern which was being investigated. A Boeing 707 had been hired from Trans Asian Airlines and despite being rather shabby, it flew safely to Kano in Northern Nigeria. The country’s second largest city is quite close to the trans Saharan trade route.

We arrived early in the morning and were surprised to observe everyone’s passport being placed onto a large pile. Gradually, a staff member would extract one, study it carefully and then pass it to a colleague sitting in what looked like a Wendy House. There was further scrutiny before the owner was instructed to receive it via a little window. We were soon on our way to Jos, where our destination turned out to be a Christian mission with a nightly separation for us. This was dramatically changed when we visited the Minister of Education, a splendid man wearing impressive robes. His secretary organized the coffee – a small tin of Nescafe and an electric kettle operated from below a large desk.

After a friendly welcome from the Minister he asked us about our accommodation. This was time for my best diplomacy and I replied that we were comfortable but not used to living 100 feet apart. His response was quite impressive. “I’m not having this, find them a house at once” he ordered.

We were driven around the countryside past the marker celebrating the highest point of 4,324 feet on Nigerian Railways. Then we suddenly entered the grounds of an attractive single storey house. It was owned by the recently established Rock Brewery which was doing so well that it was selling the same day’s production. The house keeper lived with his wife and children in a separate smaller house in the grounds.

On meeting us he recited a list of tasks that he didn’t do. We told him that nothing was required from him so we got along fine. He saw our cameras he asked us to take a family photograph which was stage managed by his wife who created a garden set and they were pleased with the result. At the end of our stay, as a leaving present, we took his bicycle to the local market to have it overhauled.

A rather interesting character was the night watchman who patrolled the grounds, armed with a sturdy crowbar and sustained by bottles of orange Fanta. It was decided by the Educational Centre that we should have a car to save the time of the driver who collected and returned us daily. I was told to apply for a drivers licence for which I was grilled with questions. “You don’t know it”, was a frequent response to my answers but probably to get rid of me, a licence was produced. The bonus was a Peugeot 504, the ubiquitous African taxi, which gave us much more freedom although caution was essential – the frequent crash scenes were marked with clumps of grass.

We were pleased with the enthusiasm of the attending teachers who appreciated Sally’s Primary school experience as a serving Leicestershire teacher. Plenty of black & white photography was accomplished by the teachers using my Nikkormat FT2 camera with processing and printing carried out in a rather hot temporary darkroom while my Nikon EL2 camera provided the colour transparencies accompanying this article. Our street photography was a risky activity with passers by claiming that our pictures would be used against the Nigerian people once we were back in Britain.

The Centre had a process camera but the diffusion transfer material it used was in short supply. A visit to the local materials dealer revealed an empty warehouse with the dealer sitting under a large umbrella to protect him from the leaking roof. An educational official was visiting England and he agreed to collect some via the Nigerian Embassy in London. Unfortunately, he carried the material through the airport Xray machine, which ruined it. The ease of enlarging or reducing artwork is taken for granted today and at a fraction of the cost for those working in the 1970s.

Before flying back to England we went north and explored Kano for a couple of days. Parts of the city are at least 1000 years old and the ancient street scene we photographed later inspired our 1979 Christmas card, a photomontage celebrating the return of the DC10 – perhaps I should have employed a parachute for a safer landing. We were very impressed by the indigo dye wells where batches of clothes are transformed by lowering them into the blue liquid to achieve a stunning transformation.

Departure night had similar qualities to our arrival. I was told to walk through the electronic gate at least four times and heard the operator call out, “I’m giving them some good checking tonight boss.” Our shiny DC10 awaited and powered its way through thunder and lightning to a chorus of screams from quite a few passengers.

Footnote

Whilst writing this article I’ve had an eye brow operation at Leicester Royal Infirmary. “What are you doing at the moment”, enquired my surgeon. “Writing an article about visiting Jos in Nigeria I said.”

“Oh I’ve been there helping to run their hospital”, she responded.

Kano Street 1979

Cactus fences, Nigeria

Bone Tools

Horse Barrow

Staff & Family for our house Nigeria 1979

Dye Wells