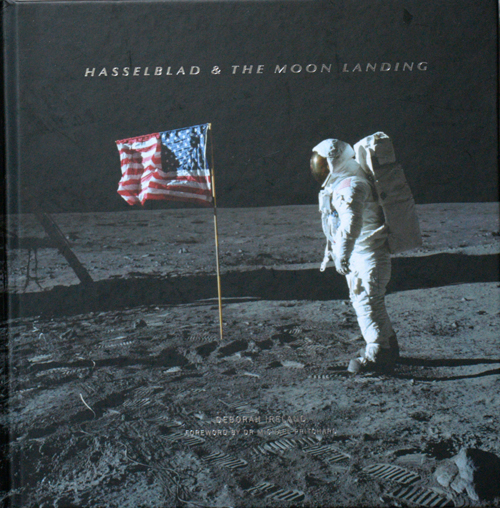

Photographica World contains many book reviews for new titles, which range from books on single camera marques such as Leica, to sub miniature cameras, photographic history, biographies of pioneers such as William Henry Fox Talbot and Niepce, and specialist subjects such as early processes (wet plate and Cyanotypes) and even cameras on the moon (Hasselblad).

Book and publisher details are included for each review, and were correct at the time of publication.

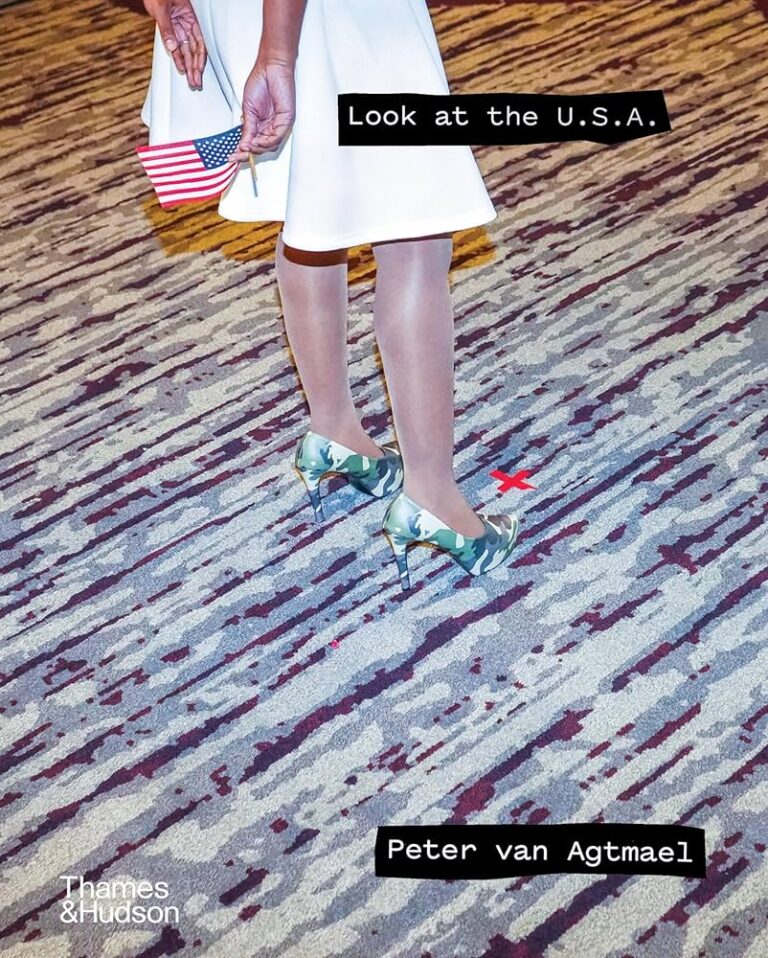

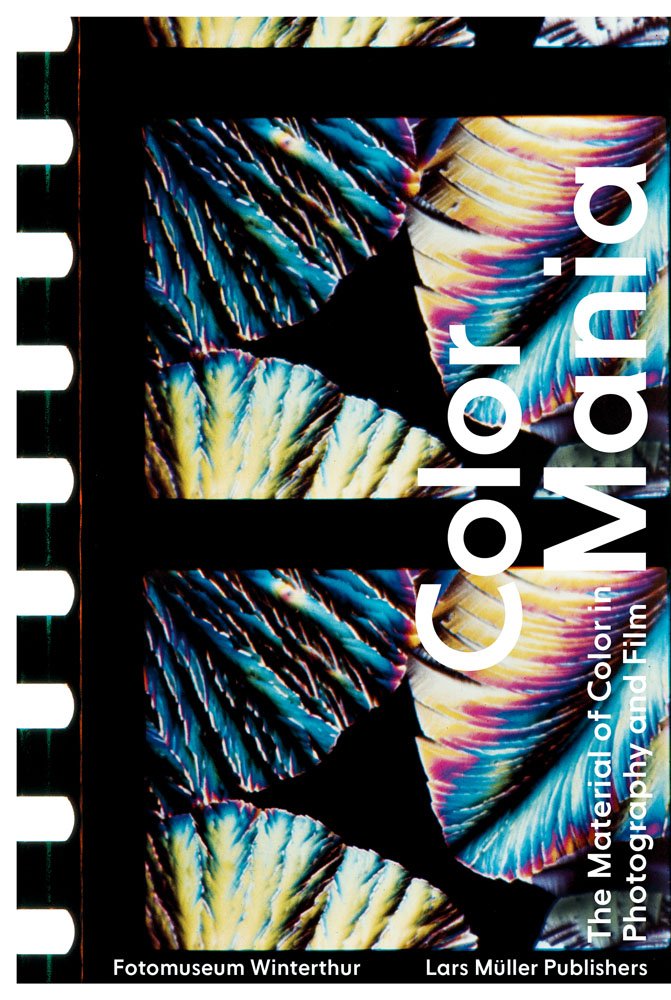

Look at the U.S.A. A Diary of War and Home By Peter van Agtmael

HB, 352 pages, 186 colour illustrations

London: Thames & Hudson, 2024

ISBN: 9780500027028

£40.00

This collection of over 180 images, all colour (in contrast to the work of Chris Chapman and James Ravilious) – visually striking, often beautifully composed, and at times, poignant, grotesque, unsettling or deeply thought-provoking – is the work of Peter von Agtmael, a member of Magnum Photos since 2008. As one would expect from a Magnum photographer, the images are consistently superb and technically brilliant. This is however a very personal collection, one that can be understood best in relation to the author’s own story, about which he provides various insights, both in the form of autobiographical episodes and fragments of family conversations.

Born in 1981 to a Dutch father and an American mother, Peter was brought up in the middle-class suburb of Bethesda, Maryland, near Washington D.C. He was nine years old at the time of the first Gulf War that followed in the wake of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. With both his father and grandfather having served in the army, he was enthralled by the patriotic military support that was widespread across America, developing the sort of interest in war and weaponry that is typical of young boys from such a background. After buying the book Requiem (1997) – a compilation of images from the French Indochina War in the fifties and the Vietnam war of the seventies, taken by photographers who had been killed during the conflict – he decided to become a photojournalist. He was studying history at Yale at the time of 9/11, which was followed by the US invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 and the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, both of which began military occupations which would last for the next two decades. Peter graduated in 2003 and shortly after won a fellowship that enabled him to travel to China to photograph the effects of the construction of the Three Rivers Dam on the Yangtze, He became a full-time freelance photographer in 2004, undertaking work in South Africa and Asia, before his first trip to Iraq in 2006, embedded with US troops in Mosul. In 2007 he joined troops in Afghanistan, and over the next few years would make repeated return visits to both countries.

It is telling that many of the photographs he took and had published did not appear in the American editions of the magazines, which printed different illustrations from the British or European issues, replacing images of the horrors of US operations in Iraq or Afghanistan with more benign pictures that they thought would be better for the readers in America. Agtmael also makes some interesting observations about the differences between British and American soldiers in terms of their conduct in the Middle East and their attitude towards embedded journalists.

The photographs themselves are by no means solely focused on the experiences of soldiers in the Middle East, although this provides a starting point from which Agtmael explores the relationship between these conflicts and social issues back home. Inevitably, a proportion of this work focuses on injury, trauma and rehabilitation, following the stories of young men struggling to adjust to their return home, whether this is due to loss of limbs and disfigurement or the disjuncture between military and civilian life.

Lamenting the psychological damage caused by these experiences might make some readers recall comedian Frankie Boyle’s acerbic comment: ‘Not only will America come to your country and kill all your people, but what’s worse is that they’ll come back twenty years later and make a movie about how killing your people made their soldiers feel sad.’ However, Agtmael’s photographs have much more to say than just to reflect glibly upon the horrors of war, and he is acutely aware himself of the tensions within his own role. Throughout the book, he reflects upon the purpose of his photography – what narrative was he trying to tell? Increasingly, he begins to regard the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan differently, realising that they could not be confined to the past as some sort of historical aberration, but that they were actually an integral part of American society, reflecting its domestic history and deeply rooted in the practices of slavery, racial violence and the genocide of Native Americans.

As the book progresses, the photographs diversify to include scenes from Serbia and Detroit, a KKK induction ceremony in Maryland, Barack Obama’s Inauguration in Washington, Native American reservations and elsewhere, drawing subtle parallels and inviting reflection. Sometimes Agtmael makes the connections explicit, such as commenting on the way in which Trump encouraged crowds at his rallies to turn and jeer at the press box, and how it recalled how he was beaten up by pro-government supporters while reporting on the demonstrations in Cairo during the ‘Arab Spring’ in 2011.

This is, therefore, a deeply personal book, chronicling the photographer’s own journey as well as that of others. It is revealing that, after he stopped embedding with army units, he became a Mentor in the Arab Documentary Photography Program, training young students in the Middle East in the art and practice of photography. Whilst this seems a natural, and admirable, response to what he had witnessed and captured on film earlier in his career, it does not seem to have in any way resolved the deep internal struggles with which Agtmael seems to be wrestling. Snippets of conversations with his family reveal their constant anxiety about his travels to conflict zones, and he describes himself as being driven at times by a ‘strange, demented urge to put my life at risk in war.’ Most war photographers could not pursue their occupation without a unique strain of psychological resilience, but they are not invulnerable; for some, like Richard Mills and Kevin Carter, it is too much altogether.

In his two-part article for the New York Times in March 2015, Karl Ove Knausgaard wrote about his travels across America with Agtmael, observing that ‘he sought complexity, not the iconic, and that this gave his photos enormous distinction.’ It’s a perceptive comment, and it is indeed this complexity which makes this book such a valuable chronicle, and one that will repay repeated readings. Many of the images are absolutely packed with detail yet tightly composed, suggesting relationships between the disparate, and often surreal elements, through a dynamic sense of movement or unusual perspectives that can startle and disturb. This is the fifth of Agtmael’s books, following on from 2nd Tour: Hope I Don’t Die (2009), Buzzing at the Sill (2016), 2020 (2020) and Sorry for the War (2020), from which some of the images here have been reproduced, alongside scores of previously-unpublished ones. It’s a remarkable body of work to date, and Look at the U.S.A. will compel the reader to do just that: but somehow America will never quite look the same again. We learn much about war, and a great deal about the U.S.A., but above all, Agtmael shows us that these two are inextricably bound together.

James Downs

A Photographic Friendship. James Ravilious and Chris Chapman.

Edited by Mark Haworth-Booth.

HB, 96 pages, 60 B&W illustrations

Skerryvore Publications, 2022

ISBN 978 1 3999 31205

£25.00

The genesis of this book was to celebrate the work and friendship of James Ravilious and Chris Chapman: two photographers with a common interest in recording the everyday life and environment of a changing world in the rural environment of Devon.

The book is divided into two parts. The first is a discussion between James Ravilious’ daughter, Ella, and Chris Chapman, the second part contains images taken by both photographers juxtaposed in pairs. This gives the reader the opportunity to appreciate the complementary facets of the two photographers’ work. In a few instances the relationship between the two images may appear rather tenuous to some viewers.

It is interesting to contemplate how far the deep sense of historical loss of times past to which Michael Morpurgo refers in his Introduction are enhanced by the fact that the images are monochrome.

Would the sadness of loss be less if the images were in colour?

The strength of the book is the way the first ‘discussion’ section brings James and Chris to life as individuals, not only as photographers but it also reflects many aspects of their personalities which they bring to their work.

This book is for reading and should not be treated as a photo album. The images should be appreciated as adjuncts to all there is to learn about the photographers and what they contribute to their work above the photographic techniques in which they patently excel. The commonality, depth of interest and empathy they clearly have for the community and environment they record is so obviously enriched by their friendship and honest appreciation of each other.

A Photographic Friendship clearly demonstrates that the relationship of James Ravilious and Chris Chapman ensured that their body of work raised the level of the ‘ordinary’ rural lives and environment they recorded at a time of change to a highly significant and irreplaceable historical archive.

Barbara Fletcher

The Ultimate Film & Darkroom Workbook, by Rachel Brewster-Wright

A4, 176 pages – monochrome

£30.00 – Available from:

https://www.littlevintagephotography.co.uk/workbook/

Readers who attended Photographica earlier this year will have seen Rachel from Little Vintage Photography selling copies of this really wonderful book.

The convenience of digital systems, equipment and processes is undeniable, and there are Apps for pretty much every pastime and hobby that you might be involved in, but traditional black and white photography and darkroom work stands firmly outside of that – and when you think about it the entire shoot/process/print workflow hasn’t really changed in 120+ years!

The digital worker can click away, safe in the knowledge that their images contain so much meta data that future appraisal of the images is a simple task. Adobe Lightroom, Adobe Bridge and other Apps allow you to see not only every aspect of exposure, camera set up, lens choice and ISO settings but also location data – a real boon as many digital photographers regularly shoot thousands of images each day.

The monochrome worker is a hugely different animal. Rarely shooting more than a hundred or so images makes it sound easy – but how do you keep accurate records of just what you shot, what gear did you use, what settings? Into the darkroom – which chemicals, development time, and temperature?

For print – paper choice, enlarger dodging information?

This is where this book comes in. In the last few years there has been something of a movement to get away from the digital environment, and to embrace a more manual approach to projects and research – known as Journalling. In effect journalling is a sophisticated way of keeping track of day to day projects, where instead of a few scribbled notes, you use a deliberate series of consistent notes and bullet points, so that as a project progresses you can see your work process from day one. This is a key point to this book, and why it is such an invaluable tool for both newcomers to monochrome photography, but also to advanced workers.

The design and layout is truly inspired, and I wasn’t at all surprised when speaking to Rachel that the final book took many years of careful refining and tweaking based on feedback from students who took part in the workshops run by Little Vintage Photography.

The heavy duty covers mean the book can take a lot of abuse, and the large spiral binding means you can fully open it out and back on itself without doing any damage. The reason that this is so important is due to the way that the book is used.

The basic premise is a 4 stage approach:

1: Record, plan & track

2: Ideas journal

3: Film & darkroom log

4: Review & reflect

By using this method the newbie builds up a set of personal data that can be referred to in future – allowing improvement and, equally important, consistency when working on photographic projects. I wish I had this book a few years ago when I was trying out the ‘Caffenol’ process – my own scribbled notes on this coffee based process are not exactly well laid out, and mean that when I go back to try it again I will in effect have to start from scratch!

The thought that has gone into the book is incredible – and it’s obvious that it has been done by a working photographer. A perfect example is that many pages have cross reference boxes – for instance you could use that to quickly find every project where you shot on HP5, or where you used a particular lens, or tried a particular film developer.

I think it’s true to say that even the most enthusiastic photographer can sometimes feel a bit uninspired or stuck in a rut. To get you out of that there are 70+ photo themed ideas to try. Still not sure? How about the chart of small inspirations?

The book uses a month by month, week by week layout, but you don’t have to stick with that. During the last couple of years I’ve been enjoying researching and trying out cameras from Lomography – building up my thoughts, film test results, even sales data and serial numbers. Having all of that in one place instead of spread all over the shop on my computer will be a satisfyingly analogue way of doing things – even if my handwriting leaves a lot to be desired!

A brilliant idea, brilliantly executed – I also recommend the ‘Sunny 16’ podcasts that are available online from Rachel and the Little Vintage Photography people – they are full of informative chat, reviews and ideas.

https://sunny16podcast.com/

Timothy Campbell

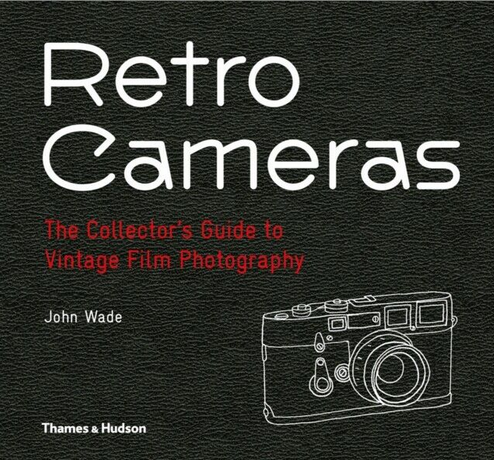

An Illustrated History of Snapshot Photography: From a Victorian Craze to the Digital Age

by John Wade

Publisher: Pen & Sword History (2024)

Hardcover: 3 x 15.6 x 23.4 cm 224 pages, fully illustrated

ISBN-13 : 978-1399079150

£29.99

John Wade isn’t the first author to write a book on the subject of Snapshots – many readers will have a copy of the book by Brian Coe & Paul Gates The Snapshot Photograph published back in 1977, but what John has done (once again!) is to take a fairly well known subject and bring it bang up to date by including not only digital equipment but also cameras that are sometimes dismissed or ignored due to their non professional or lowly amateur status.

It takes a great deal of skill to produce a book which will satisfy both the collector/historian of photographica, and the image/social observer – and John has done this in spades.

The thirteen chapters follow a strict chronological order, from ‘the first snapshot camera’ through to ‘the Digital age’, via colour, instant and even seaside photography.

The text covers a surprising amount of technical info, without ever getting bogged down, and the social aspect likewise is made clear and understandable – without being too simplistic. Given that the period under discussion includes significant technical and social changes, not forgetting a couple of World wars this is no mean achievement.

The beauty of the snapshot, in all its forms, is that it is so much more ‘honest’ than any same period professional photograph. This is illustrated here time and again, and John’s comments on some of the images does indeed make you look closer. The one that really made me laugh was of a circa 1900 picnic gathering; seven hatted ladies and gents all perched high on a dry stone wall – clutching their sandwiches while waiting for the wall to collapse!

I was amazed to read captions for a set of 6 ‘found’ holiday photos from an old album – locations for each one identified using Google Images – what a boon for the researcher that is.

How do you define snapshot photography? By the camera used? The process involved? The speed of availability?

Everything has been covered here, including excellent chapters on While-You-Wait photography, Polaroid, the impact of Kodak and the Brownie, before quite naturally ending with the ultimate in instant results from digital cameras and smartphones.

One example really did make me think of just how arbitrary definitions can be – probably 99% of readers would associate snapshot photography with simple/common cameras – has anyone else EVER considered the Hythe MkIII gun training camera as a snapshot device?! But, it is indeed a very simple camera, with minimal controls to get in the way – so does indeed belong in this book!

In many ways snapshots are the true indicator of the times – and as mentioned show a side to life that is almost never part of a professionally taken image. The professional makes sure that all extraneous matter is left out, with nothing to detract from the subject. Sadly this means that there is little to give a feel for the period. Street snapshots give the date away by the shop front signage, the vehicles, the abundance of manure on the streets and the number of people smoking! They may not add to the artistic properties, but they certainly speak volumes for the era in which they were taken.

A snapshot may be thought of as something of little value or worth, but as we all know, a humble snap can be priceless when it is of loved ones, past and present.

This really lovely book is a great reminder of that, and is also a reminder of just how vast the variety of equipment that has been used over the 130+ years is.

Full marks, John – I can’t wait for your next book!

Timothy Campbell

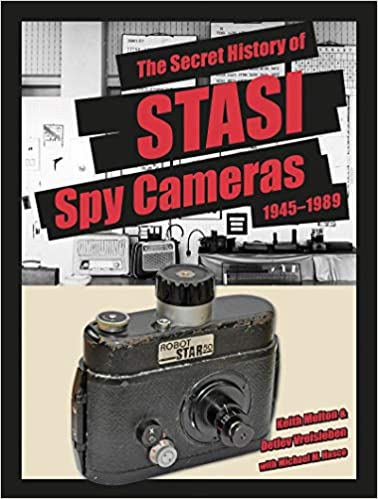

Color Mania

Edited By Barbara Flückiger,

Eva Hielscher and Nadine Wietlisbach

Paperback, 240 pages, 122 illustrations

ISBN 978-3-03778-607-9

Zürich: Lars Müller, 2020

£25.00

This book was written to accompany the exhibition of the same name held in 2020 at Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland. The theme for the project is the interactions between the aesthetics of colour in film and photography, and the underlying technologies for producing it.

The book consists of an introduction, three essays which set the scene, thirteen shorter pieces discussing the connections between the ‘ materiality’ of colour in photography and the work of particular artists, and concludes with a short conversation on the difficulties of faithfully digitising analogue colours, plus appendices. All of these are the work of different authors, many of them academics in the early stages of their careers, so inevitably the style is uneven across the book.

The word ‘ materiality’ reappears constantly; in this context it means the physical, chemical and mechanical processes and constituents which create colour in a photographic work. The contention of the authors is that the link between the materiality of the colour process and the work which has been created with it has been insufficiently researched – and that is probably true.

So for example, the mechanism and history of the Technicolor process has often been described in books and articles, and separately the ‘ Technicolor Look’ is well known to film historians and film buffs; but much less has been written about the connection between the two. On the other hand, the collaboration between Polaroid and some highly respected photographers produced interesting work that depended intimately on materiality, and has been documented.

Over the whole period of analogue photographic imaging, with a broad brush we can see that colour was desired from the start, and achieved first by hand- and stencil-colouring, then multi-negative cameras, additive screen processes, and eventually subtractive chromogenic means such as Kodachrome. The use of these overlapped greatly in time, and all were used for both still and moving images. One of the introductory essays summarises this history well.

Topics that caught my eye included

The widespread use of tinting and toning, not just in early movies where the technique was used to set the mood of a B/W scene but continuing into the era of natural (‘ mimetic’ – imitating nature) colours. Similarly in still photography, using the examples of Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole.

It’s well known that the success of the chemical industry in producing artificial dyes had great effects on the technology of photography –

ortho and pan sensitisation of B/W films, and then dyes to produce the colours in prints and transparencies. Of course these dyes were also used in textiles, and the short article on the interaction of photography and the fashion industry brought out the interaction of these two uses of dyes, supporting each other aesthetically and commercially.

The ‘ iron fist’ of the Technicolor company’s control of the filming process in the Hollywood studios using on-site colour directors, and of course controlling the complex cameras and the whole processing cycle.

The ideological control of Agfacolor by the Nazi government in Germany. This being followed post-war by aesthetic as well as business competition between Agfa and Eastman film types.

The physical appearance of the book is worth a few remarks. There is of course full use of colour, which is well reproduced. The typography of the text is plain ugly, and the arrangement of images takes some getting used to.

For most of the chapters there are illustrations with Roman numbers, which are found opposite the reference in the text, and illustrations with Arabic numbers which are full-pages split between the start and the end of the chapter. Where movies are illustrated they are always shown complete to the edges including perforations, which is necessary for the points being made by the authors. Usually two or more frames are shown – some are successive frames of the film, but quite often they are either points at which the film editor made a cut, or the book’s

producers made it seem like that by merging separate frames; it is seldom clear which, and I found that disturbing.

This book attempts an overview of the whole field, using examples from cinema a bit more than from still photography.

No surprise then that it is not comprehensive; nevertheless, there is plenty here that was new to me, justifying the underlying premise that the field is worth exploring.

John Marriage

Guide to the 1980s Disc camera

By Therese M Donnelly

Paperback, 126 pages, illustrations

ISBN 9798685025128

Precinct Press, 2020

£6.99

Against the trend the Guide to the 1980s disc camera has changed format from digital to hard copy. The original edition by Therese M Donnelly is no longer available, and this new edition was published by Precinct Press in September 2020.

After a brief survey of earlier disc formats, the enormous variety of cameras is introduced.

Donnelly lists 213 distinct models and knows of collectors who have over 300 variants. Kodak introduced four models in 1982: the 2000, 4000, 6000 and 8000. These have a sealed-for-life 9v lithium battery which could be replaced only by Kodak and which was expectedto last around five years.

There is life in the battery of my 4000, for which I paid £4: more than enough you might think.

Perhaps the most surprising technical aspect of the Kodak cameras is that they contained the first mass-produced aspherical lens on any camera.

The discs took 15 pictures of a nominal 8×11 mm (8.2 x 10.6), approximately the same as Minox cameras.

The original Kodaks had a lens with four glass elements of 12.5mm focal length at f2.8 giving an angle of view of 58 degrees (approximately 35mm full frame equivalent).

For some folk the appeal of having a really pocketable camera must have outweighed the disadvantage of the small maximum size of enlargements. Even postcard size was probably too much.

Reviewers never rated the quality of images as any better than acceptable. The first imitator was Haking whose Hong Kong made Halina cameras used an inferior three-element lens and by the mid 1980s Kodak also produced models with cheaper lenses.

Though never as popular as Kodak had hoped, they did sell 25 million cameras between 1982 and 1988 when they were discontinued. The Halina uses removable AA batteries. The most basic cameras were purely mechanical.

A common feature is a lever which

unlocks the film compartment and opens and closes the cassette to light.

The launch film was a specially formulated Kodacolor VR negative film of ISO 200. This was followed in 1983 by a HR (High resolution) version for C41. A similar film was made by Fujifilm and Boots had their own-brand film. Kodak’s sales peaked at 169 million in 1984 but film was discontinued in 1998.

There is a chapter listing the variety of features which affected the usability and now perhaps the collecting interest of cameras. The following chapter discusses values which range from an estimated £1 to over £100. Some of the rarest cameras carried advertising material. Advanced cameras included the Boots 715 which had a telephoto option. Built in electronic flash is considered to be a desirable feature.

A chapter lists the rarest and most collectible items, and a further chapter discusses accessories including underwater and tele-conversion kits.

There is a section on Miscellaneous Collectibles, including the very rare

Kodak Transparent Disc Cameras as seen at the launch at Photokina in 1982.

It is still usually possible to buy outdated film. Not discussed in the book, but for the brave there is an online template for cutting out film and reloading used cassettes.

Julian Tubbs

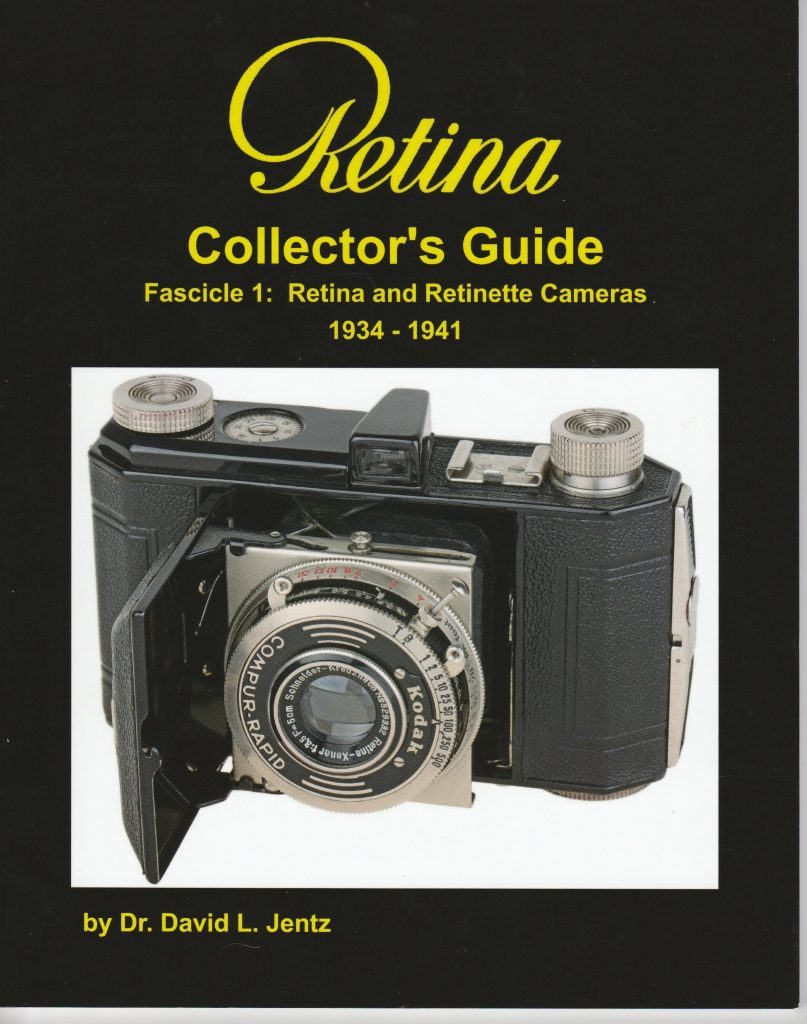

My Life as a Camera Collector

By George Schoenmann

A4, 257pp, fully illustrated in colour.

Published 2021 by the author, from whom copies can be obtained.

£20

The author described this to your reviewer as a labour of love, built up over 20 years but completed in the lockdown year of 2020.

The book is in two parts;

Part 1 is ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ and has 69 pages of stories of the adventures of a determined camera collector, full of wins and losses, of cameras from the wonderful to the dreadful.

Part 2 is a catalogue of the author’s whole collection, fully illustrated with brief notes on the camera itself and how it got into the display cabinet.

Collectors are often a bit shy about admitting what they paid for their treasures, and one of the great pleasures of this book – both parts – is the author’s willingness to lay out the successes and failures quite impartially.

Some of the ‘Good’ are probably there because they were really ‘good buys’ – bargains – rather than being remarkably good cameras themselves, though there is a healthy slice of that too. Same with the bad, the author is quite open to admitting where he paid too much, or sold the wrong thing on eBay and had to pacify his customer.

It’s quite bold, too, to have named some of his suppliers of bargains, who may, when they read this, regret the odd ‘business decision’. Who knows?

The parts on Good and Bad refer mostly to the collecting experience rather than the desirability of the camera itself. This of course makes for a whole series of anecdotes, each of which could be a mini-talk in its own right. And actually some have been, in Zoom meetings of the Club during the recent pandemic. We have all had equivalent experiences, and stories to tell; reading this part is like sitting in the bar at one of our annual gatherings and chewing over the highlights and lowlights of the year. We can envy the author his unlikely successes, and commiserate (never laugh, I hope) over the kind of pitfalls encountered and survived, sometimes with a loss of some cash or amour-propre.

When it comes to what’s ‘Ugly’, though, I don’t think all readers would agree with some of the judgments. This section is more about the cameras themselves. For instance, the author thinks that the Univex Mercury is a design monstrosity – I call it charming, attractive and as well as being very well-made (much better than most Univex products) it is a classic example of form following function, with the arched top accommodating the rotary shutter.

Interestingly, you will find that despite his dislike of its appearance he had to work quite hard to get a working example for the collection! If that’s one I don’t agree with, I should say that there are others that I do – Kodak 35, Argus Brick, as two solid examples.

Moving on to the catalogue, in a way this is a modern take on parts of McKeown’s magnum opus, though of course aligned to the collecting tastes of one individual. Know, therefore, that you will be particularly interested in this part of the book if your interests include post-war 35mm cameras,

especially Retina/Retinette, Zeiss Ikon, AKA, Olympus and Canon. All these are well represented, especially in the period 1940-1990.

There are others too – Braun, Carena, some Russians, and a variety of things such as we all have and sometimes wonder why.

The catalogue section has a standard format of illustration plus brief description for each item, where it fits in the maker’s range, what it cost and what it might now be worth. This is all potentially useful information, being real-life data most of which is local to the UK and much more up-to-date than McKeown.

The illustrations are clear, and all in colour. Although this collection is not particularly my own period of interest, I think many readers will do what I’ve done and quietly note one or two items to look out for in future.

The book has been self-published; the print is reasonably large, clear and easy to read. There are minor oddities of layout, but they don’t impact the reading experience. It’s well printed and bound, and is a substantial volume. Heartily recommended.

George, you have started a new genre of publishing here which I hope may be copied by many other collectors!

John Marriage

Women War Photographers: From Lee Miller to Anja Niedringhaus

By Anne-Marie Beckmann & Felicity Korn

Hardback, 224 pages, illustrations

ISBN: 9783791358680

Prestel, 2019

£35.00

From a German Jewish expatriate bolstering her partner’s career, to a surrealist fashion model and a Harvard graduate, Women War Photographers tracks the myriad ways that members of the ‘gentler sex’ have found themselves documenting war from the front lines. In fact, the image of war that often exists in our mind’s eye—influenced by history’s most well-known pictures of male soldiers—is not at all reflexive of the sum total of photographs taken during more than 180 years of conflict. Since the advent of photography in 1839, the gaze of women—and the inclusion of female subjects—has been conspicuously absent from our retrospective view.

Women War Photographers seeks to redress this issue by turning the lens on eight of the most important female photographers of the 20th century.

The book—a catalogue that accompanied an exhibition of 140 photographs first mounted at the Kunstpalast

Dusseldorf—opens with a short introductory essay on the history of war photography written by the show’s curators, Anne-Marie Beckmann and Felicity Korn. The core text of the book is divided into profiles on each of the photographers, followed by a selection of the photographers’ works.

It convincingly argues that although accreditation has been difficult for women war photographers, ‘our image of war…has essentially been influenced by women, too.’

Each chapter is written by different authors, offering an impressive range of knowledge on this topic. The team of authors maintains a pleasantly consistent narrative voice throughout. Sadly, the narratives are bookended by two photographers—Gerda Taro and Anja Niedringhaus—who each died in combat. Indeed, it is clear that Niedringhaus’ oeuvre—recently donated to the Kunstpalast—was the initial inspiration for the show. The final profile and image selection serve as a tribute to the German photographer (and Pulitzer Prize winner) who was shot and killed in Afghanistan in 2014.

The image selection and reproduction quality found in Women War Photographers is outstanding.

There are a number of recognizably iconic images—including Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub—as well as new works to discover.

This exhibition catalogue also includes images of the publications in which some of the pictures were first shown (in their original tones), and reproduces the headlines in their original languages—all of this to remind the reader of the normally ephemeral nature of news imagery.

The reproduction of original objects brings the reader back to the moment they may have viewed those photographs in the news.

The authors ask, then, why show war photographs in an art museum? Indeed, many of these photographers did not identify as artists or intend for their work to make it to the gallery wall. Still, we read: ‘their subtle visual vocabularies allow the photographs to reveal an even more lasting effect, to the point that have become part of our collective memory.’

Are war photographs art? No. They’re something even more interesting.

The subject matter reminds us that the gaze of these photographers is not female—it’s human. That decisive moment captured on film shows that regardless of the side you fight from, it is the war that always wins.

In fact, though some of the women highlighted in this book—notably Gerda Taro and Lee Miller—used photography to show their support for a particular combatant’s cause, each of the women demonstrates a masterful ability to use the medium to draw awareness to the plight of those affected by war.

It is not the photographers’ gender that grants them such a perspective on the human condition, but it has had its advantages. It is the women photographers who—viewed as unthreatening noncombatants—are able to gain entry into the most intimate spaces ravaged by battle. And in doing so, the authors remind us that women war photographers are able to show their female subjects, in particular, as something other than victims of war.

The photographers have agency, and they portray their subjects in the same light.

Overall, the book—offering both biographies of photographers and a perspective on the validity of 20th century conflict—promises: ‘intimate insights into everyday life during war, evidence of shockingly cruel deeds and references to the absurdity of war and its dire consequences.’ Through the above-mentioned mix of insightful text and powerful imagery, the book most certainly delivers.

Women War Photographers is a welcome addition to the historiography of war photography—a discipline that has seen excellent scholarship in the past decade.

Although in notable books and exhibitions—such as the National Gallery of Canada’s The Great War: The Persuasive Power of Photography, the Art Gallery of Ontario’s First World War, 1914 – 1918 and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath –include photographs of and by women, they don’t focus specifically on women photographers.

However, Women War Photographers is incorrect in its assertion that it is the first book and exhibition of its kind.

In fact, No Man’s Land: Women’s Photography and the First World War—an exhibition mounted at Bradford UK’s Impressions Gallery and accompanied by a book with the same name—predates Women War Photographers by two years. The show featured female photographers of the First World War next to the works of three contemporary women photographers.

Having said that, Women War Photographers undoubtedly expands our knowledge of the field, while elucidating the fact that there is still ample room to grow.

Carla-Jean Stoke

Naughty Victorians and Edwardians: Early Images of Bathing Beauties

Publisher: Schiffer Publishing Ltd (US)

Hardcover, 96 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0764321153

15.88 x 1.27 x 15.88 cm £8.95

Although published back in 2005 this book is still available online, and is one of a series of books from Schiffer that are illustrated from the vast collection of Mary L Martin, of early American postcards.

Don’t be mislead by either the title or the cover image that hints at possible sexual perversities inside – the contents couldn’t be more innocent!

The book has a only a few paragraphs of introduction, and I think it’s a shame that there is no information about the history of the postcard trade, what may or may not have been involved in the creation of the images, or which studios produced the work.

This is a pity as the key difference between these images and seaside ‘walkies’ photography is that the latter were take purely to sell as a souvenir for that individual person (or group) – these images were taken with the intention of producing a postcard, that could then be printed up in quantity and sold to any member of the public, regardless of location.

I find it slightly annoying that instead of showing the genuine postcard, each image has been given a ‘pinked’ edge design – while this (and the sandy background image of each page) gives a uniform look, it removes the originality of the thing itself. I’m sure that any photographic business creating these cards would have put some info on the reverse – even a short list of the most notable businesses would be useful for anyone finding these types of cards at a fair or auction.

The images are fascinating as they are all taken in the studio, and it’s fun to play ‘spot the prop’ throughout the book – with such things as whicker work sun bathing chairs, wheeled modesty carts, fishing nets and so on.

The garish over painting/tinting of the image adds to the overall unreality of the visual – many of them use a seascape background, with waves painted on board as the foreground – with the posed models (mostly female) larking about in between. The sense of fun is undeniable – though whether anyone thought they were taken on location is doubtful!

The selection here runs the gamut from tinted photographic studio poses, to heavily retouched images and also non photographic paintings of seaside situations. I wonder if ‘saucy’ material was ever used in American postcards, or was that strictly a british thing?

In recent years there has been great interest regarding seaside ‘walkies’ photography, and the social aspect of the subject matter based on the clothes worn, the locations used, and to a lesser degree the photographic equipment used over the years.

For anyone with even a vague interest in seaside photographic material this book (and the out of print but readily available ‘Bathing Beauties of the roaring 20s’) will be a worthwhile addition – and for the price of a small handful of period postcards, it’s something of a no brainer.

Get it/them on your Christmas list!

Timothy Campbell

Double Take: Reconstructing the History of Photography

By Jojakim Cortis and

Adrian Sonderegger

Hardback, 128 pages, 88 illustrations.

27.69 x 1.78 x 24.89 cm

Thames & Hudson, 2018. £24.95

ISBN 9780500021224

In 1999 German photographer and academic Andreas Gursky – known for his large, panoramic prints – took a series of photographs of the river Rhine near Düsseldorf. Twelve years later one of these, Rhein II, sold at auction for $4.3m, making it the most expensive photograph ever sold. Although this record price was broken three years later (with the $6.5m sale of Phantom by Australian landscape photographer Peter Lik) it generated a huge amount of interest at the time, partly due to the simple composition and abstract nature of Gursky’s image: measuring 190 cm × 360 cm, it is basically three bands of pale grey (sky, water and path) alternating with three bands of green grass – flat and almost two-dimensional in its vision. The image had also been digitally manipulated to remove details that Gursky felt distracted from the austere aesthetic.

The sale provoked the usual discussions about the artifice of the art market, the relative values of conceptual art and draughtsmanship, as well as the relationship between a photographic image and the reality that it claims to represent.

While critics and collectors debated these points in the art journals and press, two Swiss photographers – Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger – took another approach, and set about trying to recreate Gursky’s two dimensional image by constructing a three dimensional model in their studio in Zürich. Intrigued by the results, they began attempting to do the same for other famous photographs, being drawn especially to those that captured moments of historic significance.

The dioramas are all hand-made and use a range of materials, glue, wires, pieces of cloth, papier-mache, painted card and so on, painstakingly assembled over two or three weeks. Hundreds of digital photographs are taken, allowing for constant visual checks on progress. Usually by around 500 photos, the image is just about there, but the duo will typically take about a thousand photos before they are satisfied that the reconstruction is as close as can be. Some of the sets were constructed on tabletops, while others were constructed on their studio floor and were over twenty feet in length. Twenty such models were created for their first project, with an additional nineteen made for this book.

The illustrations in the book are of the reconstructed images, shown in situ within the studio, and are arranged in chronological order, beginning with Nicéphore Niépce’s 1827 heliograph, ‘View from the Window in Le Gras’, and ending with an anonymous tourist’s photo of the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004. The selection includes Fr. Francis Browne’s photo of the Titanic leaving Cork harbour (1912), Ernest Brooks’ ‘Five Soldiers Silhouetted at the Battle of Broodseinde’ (1917), Harold Edgerton’s strobe-lit ‘Milk Drop Coronet’ (1957), Mao Zedong swimming in the Yangtze River in 1966, Buzz Aldrin’s photograph of his bootprint on the moon (1969), and Natalie Fobes’ aerial shot of the grounded oil tanker, the Exxon Valdez (1989). Of the 39 historic photographs that have been reconstructed, almost half are images of war, assassination, terrorist activities and deadly disasters.

While the cultural impact and significance of many of these images cannot be doubted, their representation here seems somewhat disproportionate – one might have expected a selection of forty-odd ‘iconic’ images from the history of photography to avoid leaning too heavily in one direction. There is a great deal of playfulness and visual humour in the way that the photographers have reconstructed some elements of the past, but this sits somewhat uneasily with – for example – images of torture in Abu Ghraib or the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11.

Each image is accompanied by a paragraph on the facing page, providing some contextual details about the original image (rather than the reconstruction that is shown.)

Additional photographs elsewhere in the book show some of the stages in constructing the models, with views of the studio set-up that show some of the complex challenges faced by Cortis and Sonderegger.

Surprisingly perhaps, there is not a great deal of attention paid to the practical details of how the dioramas were assembled, and it would have been interesting to have at least one in-depth illustrated account of this process.

There is, however, an introduction by Florian Ebner, an essay by Christian Caujolle and a seven-page interview with the photographers by William A. Ewing.

Double Take provides an intriguing series of revisits to familiar and icon images from the history of photography, as well as challenging the reader to think more deeply about the complex and uneasy relationship between the photographic image and the reality that it claims to represent.

James Downs

Photopoetry 1845–2015, a Critical History

By Michael Nott

New York/London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts 2018

Hardback, xii + 292 pages. 56 illustrations

ISBN: 9781501332234

Michael Nott’s fascinating study of ‘photopoetry’ explores a range of different textual collaborations between photography and poetry, whether these are amateur experiments with Victorian scrapbooks, a single person combining their own words and images (less common, and only touched on lightly here), a joint project between an individual poet and a photographer that they know, or a more retrospective publication in which photographs and poems are brought together from different time periods, be they amateurs or distinguished practitioners. Although much has been written about the relationship of photography and literature in recent years, and the history of the ‘photobook’ has been documented in detail by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, this is the first work of this kind to focus exclusively on poetry. It is above all a book about relationships – between photographs and poems, between writers and artists, and more generally between the written word and the visual image.

There is of course no space in a book of this size for a comprehensive survey of every such collaboration since 1839, and Nott’s selection is limited to the English-speaking world, based on works in which the collaboration is of historical or cultural significance – rather than the quality of the photographs or poetry. There are five chapters, which follow a roughly chronological structure as they cross to and fro the Atlantic.

Chapter 1 examines the origins of British photopoetry between 1845 and 1875, beginning with an anonymous scrapbook in St Andrews University Library that contains six pasted-in calotypes of a young woman, each accompanied by hand-written, original verses. It has been given the title A Little Study for Grown Young Ladies, Illustrated Photographically – the first known use of the phrase ‘illustrated photographically’, which would be used increasingly over the next few years in printed editions of the works of poets such as Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth. Nott discusses the St Andrews album in detail, suggesting possible identities for the photographer and the young woman who appears in the staged images, before moving on to consider later ‘photographically illustrated’ editions of poetry, the composite photographs of Henry Peach Robinson that were combined with verses by the likes of Arnold and Shelley, as well as the famous collaboration between Tennyson and Julia Margaret Cameron on Idylls of the King and various lesser-known works by T.R. Williams, William Morris Grundy, Thomas Ogle and others, including the pictorialist photographs produced by Philip Henry Delamotte for The Sunbeam: A Book of Photographs from Nature (1859), and those of Mabel Eardley-Wilmot that illustrated Songs from the Garden of Karma (1908) by the Anglo-Indian poet Adela Nicolson[‘Laurence Hope’.]

Chapters Two (1875-1915) and Three (1913-56) are devoted to American photopoetry, showing how Americans at first copied the conventions that were popular in Britain – typically nostalgic and rural or pastoral – before rapidly developing a more modern, cosmopolitan form. Key works include the collaboration between Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley and photographer William B. Dyer, six photographically illustrated books by black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, the classical tableaux of Lejaren à Hiller and Kendall Banning, as well as Adelaide Hanscom Leeson’s illustrations for Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Nott then moves on to discuss the ‘imagist’ poetry of Ezra Pound, showing how his modernist techniques of writing were influential in shaping the relationship between text and image in 20th century American literature, and using this as a basis to explore collaborations such as that between Hart Crane and Walker Evans in The Bridge (1930), and Rudy Burckhardt and Edwin Denby in Mediterranean Cities (1956).

Chapter Four returns to postwar Britain, examining the period from 1957 to 1994 with prominent attention given to Ted Hughes and his work with photographer Fay Godwin e.g. Remains of Elmet (1979), as well as an intriguing collaboration between poet Thom Gunn and his photographer brother Ander Gunn in their book Positives (1966) which explores the urban landscape of London, and the Orcadian work of George Mackay Brown and Gunnie Moberg. On theme that emerges in this chapter is the relationships between people and place, and how the earlier British preoccupation with picturesque and pastoral themes was gradually transformed by growing concerns about the meaning of home, exile, and belonging.

A related movement is also evident in the fifth and final chapter, which covers the period from 1992 to 2015, a period in which – Nott suggests – there was a move towards focusing on objects rather than places. In support of this, he looks atwork such as Sweeney’s Flight (1992) – Seamus Heaney’s collaboration with photographer Rachel Giese – poet Paul Muldoon’s work with photographers Bill Doyle (Kerry Slides in 1996) and Norman McBeath (Plan B, 2009), along with the latter’s book Chines Makars which was produced with Robert Crawford (2016) and Hiding in Full View (2011), a photobook collaboration between poet Don Paterson and painter Alison Watt, in which each image was inspired by the photography of Francesca Woodman.

Even this sweeping survey of a selection of the ‘photopoetic’ works under consideration here will give some idea of the wide range of Nott’s reading and the richness and diversity of his choices. Even those familiar with some of the names of photographers and poets may not have realised that they have worked together, and Photopoetry 1845-2015 will inspire many readers to seek out these publications or at least think afresh about the relationship between photography and poetry. Although some of the book employs the technical language of academia, this is a very readable history that rarely strays far from the lives and works of those under discussion, prioritising detailed analysis of the words and images on the printed page. With over 50 B&W illustrations and numerous quotations from over 170 years of poetry, there is much here to enjoy for anyone interested in photography, literature and – of course – the way in which the two continue to engage and interact.

James Downs

A photographic journey through the london underground

by Elke & Nico Rollman

A4 landscape, Hardback

150 pages, fully illustrated

ISBN 978-1526781086

Pen & Sword Transport, 2021

£25.00

This photographic book contains images taken on the iconic London underground between 2007 and 2021 and really is a very keenly observed series of images.

The co-authors are German born but are London based, and clearly have a fascination with the many visual facets of the subject.

The book contains 18 chapters including Architecture, Ornaments, Stairs, staircases and escalators, Safety, People, Trains (naturally) and possibly my favourite – Ghost Stations.

Sadly there is no information on the equipment used for the photography, but as there are no serious colour casts from the multitude of light sources in many shots, I assume it to be digital. Whatever kit was used the quality is uniformly excellent and the majority are very nicely observed and captured. With such a vast subject matter there is always the danger of content being there for completeness, and for me this is the case for certain images. The shots of buskers are little more than snaps, and could have been taken by just about anyone with a smartphone, and the same can be said also of various workmen – although the latter do at least show the kind of work that goes on behind the scenes.

However that criticism aside, there are some beautiful photographs on show, and do inspire this reader at least to pay more attention next time I visit ‘the smoke’.

My personal photography style has always been in abstract shapes, patterns and textures and there are many examples contained that tick that box for me. Although I’m not a regular visitor, I’m amazed that I’ve never noticed the wonderfully ornate tiled surround of the ticket office at Edgware Road, or the green opulence on display at Regents park. Maybe next time I should start thinking like a tourist and take some snaps, rather than rushing along, head down, trying to act like a local!

Each chapter has a couple of pages of information and history, so while never intending to be the definitive book on the subject, these do add a nice , easy read to go along with the photographs that follow.

One of the things that struck me while reading this book was that the London Underground is one of those entities which is in a constant state of change, while at the same time retaining it’s very earliest parts.

The chapter on ‘Shut Down’ links images of stations that are closed for repairs, closed for the one day that the underground doesn’t run (Christmas day), or closed for good! The shot of the closed doors at Barons Court are framed by an art deco looking awning/sign, and above and behind that carved onto the building itself the huge lettering ‘District Railway’ which is most definitely several decades earlier!

So often buildings and facilities have their period details removed, or at best, plaster boarded over – it’s quite jolly to see this kind of mis match in fonts, colours and styles – but it somehow remains iconic. Having said that there are also photos of signage from all corners, and personally I’d replace them all with circa 1900 examples, but sadly that modern, high reflectance figure and text for ‘Fire Exit’ must be used to keep within current guidelines!

The Underground has often been used as a way of sharing the arts – using the inside space to display short poems is one way, and the other is the installation of ‘artworks’ at the stations themselves. The series of mosaics shown from Leytonstone Station and others are superb, and what works so well is that there is no scale of reference, which makes them both abstract and intriguing. The one of the shower scene from ‘Psycho’ with a profiled Hitchcock lurking is sublime. Ditto the aircraft tailplane detail from Heathrow and people on escalators at Oxford Circus.

So much to see, so many tube stations!

The installation image from Gloucester Road shows just what a well thought out, expertly taken photograph can do.

A landscape shot from (probably) the opposite platform, this image shows three people on a bench, each equally distanced from the other (how very British), another person standing to the side and yet another figure walking along, a blur in the background. There is a huge display of curious figures that is arranged within the archways of the station to the back. This one photograph creates so many questions in my head – does anyone know each other, are they happy/sad/fed up, are they going or are they arriving? Have they even noticed the display behind them?

I mentioned the Ghost Stations chapter – the photos for these disused buildings are ok, but personally for such a sequence I’d have chosen more atmospheric lighting. Some of them just look sad and neglected, whereas they could have been made to look truly weird with either supplementary lighting, or just choosing sunrise r sunset for a bit of atmosphere – but that of course is just my personal taste.

The book wraps up with a decent list for further reading, although I noticed these are nearly all titles from 2000 or later, and there is also a nice selection of films listed that use the Underground as part of their plots. For sci-fi oddness I’d go for the 1967 classic ‘Quatermass and the Pit’; to guarantee you’ll never go into a seemingly empty tube station I recommend ‘An American werewolf in London’.

This book is subheaded ‘LOOK AGAIN’ and I am sure that having read this book, any reader will do just that the next time they get the chance to ‘Mind the Gap’!

Timothy Campbell

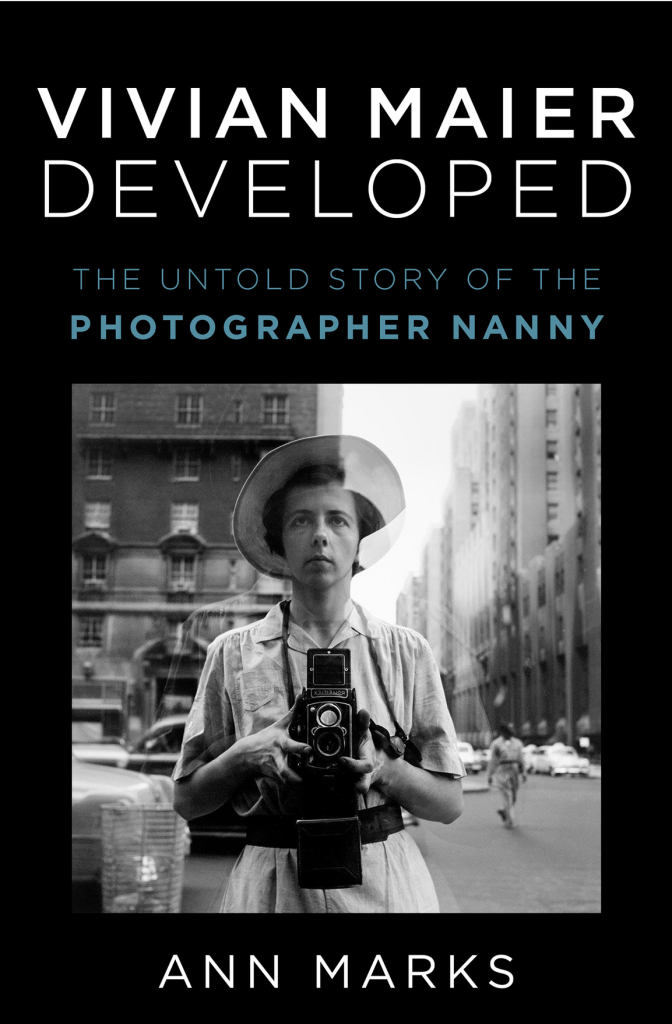

Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny

By Ann Marks

Atria Books, 2021

Hardback, 368 pages, 15.56 x 3.05 x 23.5 cm, ca. 400 illustrations

ISBN 978-1982166724

Price: $40.00

The discovery of Vivian Maier’s photographs is a remarkable story. In 2007 the contents of some storage containers were put up for sale due to non-payment of the rental fees. Three amateur collectors purchased an unseen selection of negatives and prints, some of which were then shared online. There was little interest, and nothing known of the photographer, until one of the collectors linked the name on a box with a death notice published in the Chicago Tribune in April 2009. Gradually, pieces of the puzzle began to fit together, more of Maier’s work was identified and published, and her skill as a photographer received widespread critical acclaim that has continued to grow ever since.

Her body of work is impressive – around 150,000 negatives, many of which she never developed, mostly B&W images taken on the streets of Chicago or New York with a series of Rolleiflex cameras (she bought her first one in 1952), or occasionally later in life, a Leica IIIc, Zeiss Contarex or Exakta. Her photographs juxtapose the finely-dressed and the destitute, capture children at play in the streets, crime scenes, intimate moments in doorways, parks and beaches, human interactions in street cars and outside shop windows, priests and nuns taking part in religious activities, as well as more conventional portraits, glamour shots and records of worldwide travel.

In many of the photographs she appears in reflection, or as a shadow cast across the foreground, and this ambiguous sense of presence – coupled with the story of how her photographs had been hidden away for years, undeveloped and unseen – created a sense of enigma about Maier, who was then presented as some sort of sad and lonely eccentric. A film, Finding Vivian Maier (2014), did much to boost her posthumous reputation as a skilled street photographer with a unique artistic vision, but the documentary raised as many questions about her life as it answered. Although the buyers who had acquired Maier’s negatives did their best to promote her photographic work (the financial, legal and ethical issues surrounding this continue to be debated intensely), they were unable to discover much about her life – a gap that this biography has definitively filled.

Ann Marks, a retired executive and marketing officer for the Wall Street Journal, might seem an unlikely biographer, but her curiosity was stirred after watching the documentary and she began using her research and analytic skills to find out more about Vivian’s history. With painstaking effort, she tracked down people who had known her in Chicago and New York, surviving relatives in France, as well as genealogical, medical, prison and state records in the archives. This has resulted in a minutely detailed, candid but sensitively-written account of the photographer’s often difficult life.

She was born in 1926 in New York City to French Catholic Marie Jaussaud Justin and Austrian Lutheran engineer, Charles Maier. A mismatched and unstable couple, their marriage was not helped by the birth of Vivian’s older brother Carl in 1920. With their father often absent for long periods, Marie took the children back to France to live in the Alpine village of Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur near her mother’s relatives. Through family friend and photographer Jeanne Bertrand, Marie acquired a Lumière Lumibox in the early 1930s with which she took the first known photographs of Vivian.

Her childhood and teenage years were spent alternating between rural France and inner-city Bronx and Manhattan, while both her mother and brother suffered from mental illness. Carl was later imprisoned. Following the death of her grandmother, Vivian returned to France in April 1950 to sell the family house, then travelled around France, Switzerland, Spain and Italy with a box camera similar to her mother’s, taking and developing thousands of photographs. Aged 25, she returned to New York and began work as a nanny, a job she would continue for over 40 years.

This early life is worth recounting here because it dispels much of the sentimental mythology that portrayed Maier as some sort of eccentric and reclusive amateur. In contrast, Marks argues that – while these childhood traumas clearly damaged her social and relationship skills, they also taught her to be self-reliant and entrepreneurial, determined to learn the practical skills that would provide her with independence. Chapter Six also reveals that she had not intended to remain an amateur, but used her acquaintance with two neighbouring female professional photographers to gain experience and introductions to the network of commercial photographers in the area. At the School of Modern Photography on 57th Street she developed her first colour film in 1953, met professional photographers (taking many of their portraits too) and began exploring the possibilities of commercial work: she pursued advertising, fashion and paparazzi-style opportunities, sold some of her prints, developed a business plan for a photographic postcard business and was also paid by parents to take portraits of children in her charge.

She left New York for Los Angeles in July 1955, but when the opportunities presented by Hollywood failed to materialise as she’d hoped, Maier took a job in Chicago in 1956, where she would remain for the rest of her life. She returned to New York on only a handful of occasions, but in 1959 she travelled across Europe, North Africa and Asia, with her camera. Her street photography in Chicago in the 1960s overflows with visual humour, creative ingenuity and her ever-present sympathetic interest in issues of race and class. She began using a Leica, and also experimented with home movies and tape-recorded conversations. Her life became less stable in the 1970s and 80s, with frequent moves and increasing disorganization in her personal and financial affairs, before she finally retired in 1996 at the age of seventy. She took no photographs after 1999, and died in 2009 following a fall and head injury the year before.

With eighteen chapters, four appendices and information boxes providing – for example – lists of celebrities photographed by Maier and titles of the books on her shelf, Vivian Maier Developed should provide readers with all they need to know about this fascinating individual: and with some 400 illustrations in colour and B&W, generously reproduced at large size, the book also allows readers to savour Maier’s unique photographic skills.

James Downs

RAF in Camera: 100 Years on Display

By Keith Wilson

Publisher: Pen & Sword Aviation

Hardcover : 472 pages

ISBN-13: 978-1526752185

21.59 x 3 x 27.79 cm £38.00

As a kid I was seriously into aircraft – or more accurately I was into looking at images of aircraft, and in particular the design of them (oddly enough commercial aircraft left me cold!).

This truly superb book has given me that same sense of wonder, excitement and thrill that I enjoyed as a 9 year old.

The book is broken down into chapters such as Pageants and Parades, Faster, higher, further, Royal connections etc, each one showing a photographic timeline of airaft of the RAF across the 100 year span. Needless to say the image quality of the very earliest pale in comparison to the more recent stuff, but for atmosphere, nostalgia and a feeling of ‘seat of their pants’ flying those early ‘teens photographs are pure gold.

What I especially enjoyed is the various birds eye views of airfields of those vintage days, with a huge mixture of known, and not so well known aircarft all cheek by jowl.

The scale of some of the planes is almost staggering. The tiny power of even the biggest engines back then meant a proportionately huge pair of wings were required to generate lift – in some photos a single wheel totally dwarfes the ground crew who are stood next to it. How any of these giants ever flew is beyond me.

Those early days are equalled (in my view) by the golden period of the 1950s. I was lucky enough to visit airshows in the early/mid 70s when you could witness a lightning, a Vulcan, a meteor and a Vampire, all flying by at seemingly head height, on full power – never to be forgotten, that experience is recaptured in the stunning air to air photography in this book.

I do need to point out that there is no information at all about equipment used, the photographic technology that would have been used across the 100 year span, or any details of how you arrange to be in the right position, camera ready, when you are pulling 9 G at 35,000 feet while keeping an eye on your neighrbours wing tips that are often within yards of your own.

The recent photographs include stealth planes, fuel tankers, Hercules etc – nothing has been left out.

The text is very well written, with an intro page or two for each chapter, but a lot more information and detail is in the blurbs for every photograph.

Author Keith Wilson has written a perfect tribute to the RAF, and the image quality and excellent print and binding make this a must have book for anyone with an interest in the history of aircraft in the RAF.

Timothy Campbell

The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures

by Paul Fischer

Hardback 392 pages with illustrations

ISBN 978-0-571-34864-0

Faber & Faber, 2022

£20

Subtitled ‘A true tale of obsession, murder and the movies’ – this utterly absorbing, and at times heart breaking biography of Louis Le Prince has all the elements of a blockbuster movie – exotic and not so exotic locations, a genius/visionary heroic inventor, an assortment of side characters all trying to achive a similar goal, and an immoral egotistical villain the equal of anything in the James Bond franchise.

The book is laid out in a similarly cinematic fashion, the opening sequence being the monumental day in 1888 that Le Prince arranged his family in the garden of their house in the Roundhay area of Leeds to create the first ever single camera moving film sequence, a jump cut to the train station at Dijon 2 years later where Le Prince waved goodbye to his brother and niece on his way to Paris, a dissolve to the image of his wife and family waiting and hoping that he might be on the next steamer due in at New York, and slow zoom in on the evil at the centre of the murderous plot.

The birth of moving pictures is yet another of those occassions that happen in history, where several people, continents apart, are all working on a common goal at more or less the same time. What is so very sad about Le Prince was that he was truly the originator, the genuine genius with an incredible future vision of what would become everyday, and set out on a road to that, all the while knowing that the stuff that he needed to make it work (celluloid) did not yet exist.

Author Paul Fischer does a great job in explaining the technical limitations of the time, without getting bogged down in too much technical detail. He covers the work and importance of Marey and Muybridge, and also explains their approach to capturing and demonstrating movement as that is vital in understanding just how different was Le Prince and his goals for producing moving pictures.

The way he sketches out the villain of the piece (Thomas Edison) is a masterclass in characterization, and his hateful spirit is ever present throughout the book. Edison used his knowledge of patent laws to not only protect his own half baked ideas, but also to issue ‘caveats’ in case someone else came up with an idea that had potential. Any time he got wind of a new invention, he’d issue a caveat that implied that he had thought of it first. Sadly by the time of Le Princes sucess (in getting a fully working movie camera and projector designed and built), Edison was such a powerful (and rich) figure that no-one dared to take him to court. Lizzie Le Prince did so in an attempt to show (quite rightly) that her husbands work, his equipment and patents all predated Edison by well over a year, and also that Edisons pathetic peephole ‘what the butler saw’ was in no way the same technical advance as Le Princes… she lost.

Covering the back story of the Le Prince family, and explaining how Louis met his future wife, and their eventual settling in Leeds, the future inventor of movies is painted as a cultured, patient and loving man, quotes made at the turn of the 20th century by former employees show him to be considerate, hard working and clearly a man with a mission.

It is almost agonising reading his letters to wife Lizzie during the whole process of his efforts to get firstly a ‘movie’ camera made (the ‘easy’ bit!) and then a projector for the filmed sequential shots. It is hard to imagine that the only solution until the invention of celluloid was for Le Prince to build a 16 lens camera, that used solenoids to act as shutters to expose a single glass plate. The resulting frames were then individually transferred to a hand made

ribbon that had perforations along both edges to allow the images to be moved in sequence, held briefly in position behind the projecting lens, all at (a hoped for) 16 frames per second.

That the early machines were noisy, clanking brutes and resulted in frequent jams and shattered images is hardly a surprise. Le Prince also tried paper roll film, but this was prone to tearing and had a much softer image, so again was not the right medium. Once celluloid was produced it was the answer to Le Prince’s prayers, and within a short time he had a single lens camera ready, a reliable projector made, half decent patents in place and was ready to pay a short visit to his brother in Dijon, tootle along to Paris to sign the patents, then quickly whizz back to Leeds to see Lizzie, then over to Liverpool and on to USA for fame and fortune… he got on the train at Dijon, but never arrived in Paris.

The story of Le Prince has been written about before, most notably in 1990, ‘The Missing Reel’ by Christopher Rawlence, but until now this most curious case has remained unsolved, with various possibilities being considered.

Did Edison send an agent to get rid of Le Prince before he could get the all important patents fully registered?

Was it Edison himself who threw Le Prince off the train, his body never to be found?

Was Le Prince so mentally frazzled with his years of effort that he did himself in, leaping from his carriage at some remote spot part way between Dijon and Paris?

Paul Fischer considers every possibility in almost forensic detail, and you can’t help but get swept along with each of them, before they are dismissed. The final solution revealed makes absolute sense, and it seems odd that it’s taken this long for someone to propose it.

The level of detail in this book is outstanding, with the legal machinations expertly explained, without ever getting tedious or dull.

For me the long lasting impact is the cementing of my disgust for one of the Worlds most successful ‘businessmen’ –

who clearly did not know a good idea even when he was accidentally sitting on it.

It’s fascinating to map the various places where Le Prince set up home and workshops over a period of years – and although the buildings are no longer in existence, the locations are easy to pinpoint, including the family home in Roundhay and the workshop on Woodhouse lane (opposite the main entrance to Leeds university), and the house off Park Square in central Leeds.

There are commemorative plaques near to Woodhouse Lane (now a BBC studio) and most significantly by the bridge in Leeds where the footage of traffic was filmed in 1888.

A totally engrossing book, as good as the very best Agatha Christie novels, and as enthralling as a Hitchcock movie.

Timothy Campbell

Picturing the Western Front: Photography, Practices and Experiences in First World War France

By Beatriz Pichel

Hardback, 272 pp. 43 illustrations

ISBN 978-1-5261-5190-2

Manchester University Press, 2021

£80.00

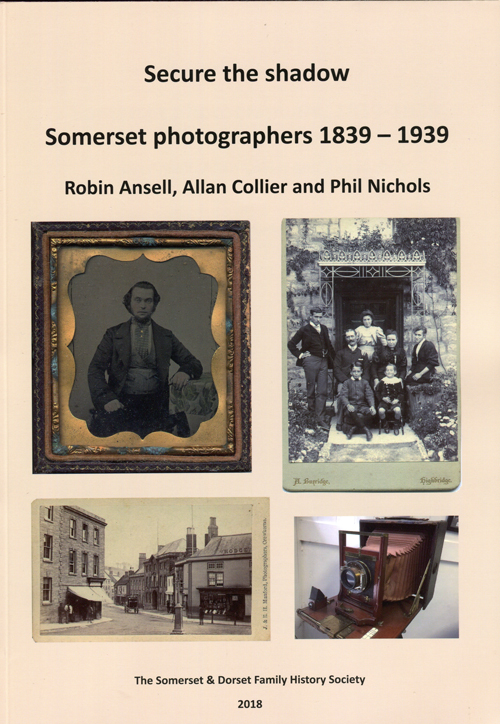

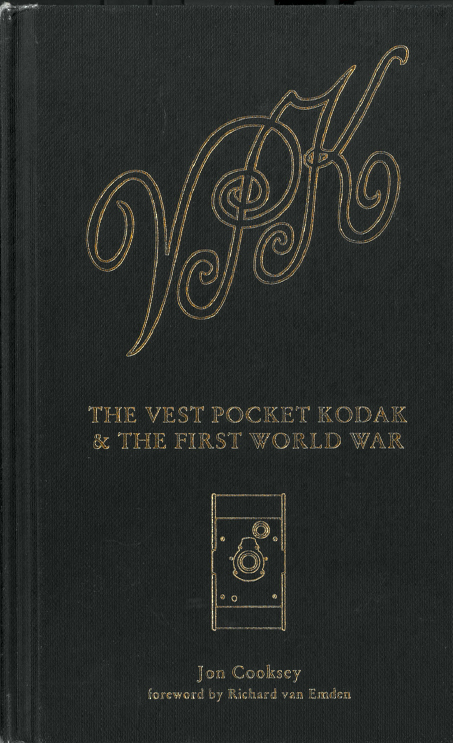

Photographic images from the First World War are far from unfamiliar. Recent issues of PW have included articles on Frank Hurley and Charles Lesage, as well as a review of a book on wartime use of the Vest Pocket Kodak, while the 1918-2018 centenary prompted an avalanche of commemorative articles and picture galleries that were prominent in the media for many months. Sometimes readers become so familiar with these photographs as illustrations or symbols that we lose sight of the fact that such ‘visual content’ comes from a physical material – such as a paper print in an album, or a glass slide – and, furthermore, don’t stop to think about how, why or where these photographs were taken.

In her new book Picturing the Western Front: Photography, Practices and Experiences in First World War France (Manchester University Press, 2021) Dr Beatriz Pichel examines some of the many thousand pictures taken by military, press and amateur photographers between 1914 and 1918, and considers how war experiences were shaped by photographic practices.

Doing photography (taking pictures, posing for them, exhibiting, cataloguing and looking at them) allowed combatants and civilians to make sense of what they were living through.

In the introduction, the author tells the story of WWI veteran Gérald Debaecker who gave his wife a photograph album in September 1920 to mark their first wedding anniversary.

The album included photos from both their wedding and their honeymoon, during which they had travelled through France visiting places in which he had fought during the war; the album also had portraits of him taken during the war in the same spots, as well as photos of the couple revisiting the place where had been wounded, and almost re-enacting events for the camera.

In microcosm, this album encapsulates many of the themes of this book – the complex, nuanced and sometimes surprising ways in which individuals use photography to make sense of their experience of war.

The photographic practices in question are not merely the act of taking pictures, but also posing for the camera, collecting, exhibiting, arranging, cataloguing, captioning and looking at photographs. There are countless books on war photography that consist almost entirely of representation – using images as visual records of events – but this is the first study to focus attention upon the role played by photography itself in the experience of armed conflict.

The book comprises five chapters, the first of which, ‘Recording’, looks at the way official organisations such as the French ‘Section photographique de l’armeé’ (SPA) tried – and failed – to control photography, seeking to regulate the photographic practices of amateurs and create an official narrative record of the war. Attention is given to the way photographers were commissioned or licensed to operate at the front, and how photographic archives were categorised, preserved and arranged. This chapter, like much of the book, is based on extensive research in French archives, and also includes some interesting discussion (pp.46-8) of the various cameras used in the field and the factors influencing these choices.

Chapter Two, ‘Feeling,’ considers the emotional aspects of wartime photography, such as the ways by which the practise of photography domesticated life on the front line. Combining sensitivity with thoughtful analysis, the author looks at the reasons why soldiers might have taken photographs of routine tasks such as cooking meals, reading or posing in the trenches with photographs of loved ones, or why medical staff preserved photos of injured officers receiving treatment in field hospitals. There are many amusing images, when soldiers entertained themselves by dressing up in costume and clowning for the camera, and it is interesting to consider how the communication of such images – those sent home to families, and those received in the trenches – managed to link the horrors of war with the domestic sphere of family life back home. One topic that is often overlooked is how wartime photographs were displayed at the time, and how viewers of these images were expected to engage with different sorts of photograph. One of the many fascinating illustrations in the book is a photograph from an SPA exhibition in Biarritz in 1917, which shows a woman looking through a stereoscopic viewer and presumably experiencing a form of immersive 3-D experience in doing so.

It is perhaps worth mentioning that many of the illustrations are too small to make out much detail, which is a shame when there some fascinating images from photographic archives that have never before been published.

Inevitably, war involves injuries and suffering, and Chapter Three, ‘Embodying’, focuses upon how photographers handled the traumas inflicted on the human body. These include representations of facial surgery, portraits of soldiers who had lost limbs and the possibility of them finding work as invalids, and the taboos and censorship issues surrounding the depiction of the dead – and how these principles differed in the case of enemy corpses.

This chapter is linked closely with the following one, ‘Placing,’ which discusses issues of location and geography, revealing how both combatants and civilians identified with the damaged landscape. Images of ruined churches and devastated woodlands could be used for propaganda purposes, while stereoscopic photography could provide an enhanced visual sense of the physical environment for those who were not present. Efforts by the SPA to systematically record the devastation wrought by war on French villages and countryside suggests some parallels with the work of the 1850s ‘Mission héliographique’, organised by the Service des monuments historiques (SMH) to document France’s architectural heritage.