PCCGB

Along with new book reviews, a regular feature in our club magazine Photographica World has been ‘Classic Bookshelf‘. It can be interesting to note how attitudes and ideas change over time, so rereading an older book can be an invaluable way of comparing ‘then’ with ‘now’. Some of the books reviewed are relatively recent, some are well over a century old.

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

read the review

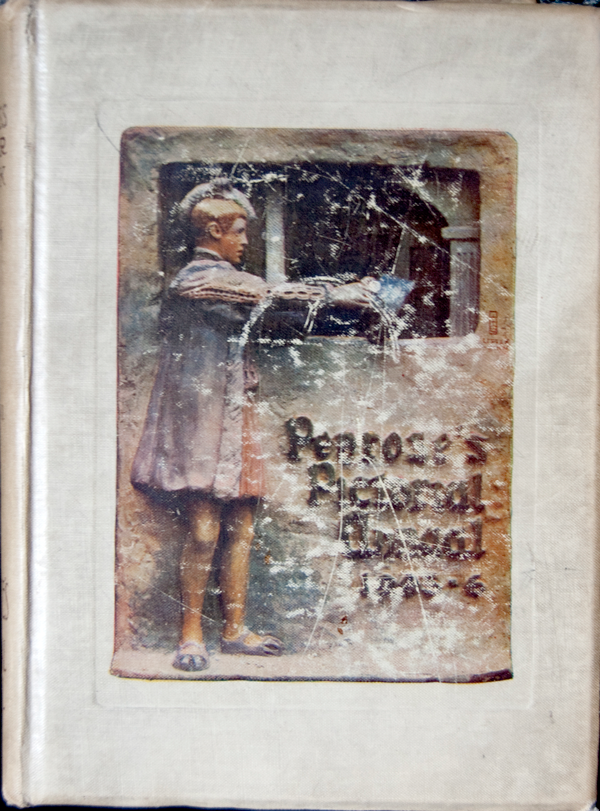

‘Photography with roll films’ – the Primus Handbook

1903 – the Country Press, Bradford

7×5″ – Hardback

196 pages, plus adverts & inserts

Although a truly life long lover of 2nd hand books and bookshops (I started browsing at the age of 8), it’s only recently that I’ve allowed my collecting to creep earlier than the 1950’s – for me the ‘year zero’ (or technically speaking ‘decade zero’) of all that is photographically inspiring and thrilling – both visually and gear-wise.

There’s something wondrous in spotting a book spine on a shelf that makes all thought go out of your head, that makes the other titles fade away and that connects directly with you – as if it has been sat there waiting for you to pick it up – and leaves you unable to walk away without it.

This particular title I purchased at the rather posh antiquarian book fair that’s held at York racecourse – and it’s possibly the only sensibly priced book that was for sale. It was nice to see a first edition of Cartier Bresson’s ‘The Decisive Moment’ (French language edition – so not actually titled ‘The Decisive Moment’!) but in tatters, pages falling out – for only £750?

The spine of my book is quite faded so it’s quite lucky that I managed to make out the very period type face and titling, but as soon as I saw the cover illustration I knew I had to have it – a more ‘art nouveau’ lady I’ve yet to see!

Most collectors know the value in having either magazines or year books for getting exact info on the availability and specs for certain cameras and kit – the Primus Handbook is no exception. It’s front and end pages are literally jammed full of lists and illustrations of all manner of gear and (for me) most interestingly for film and processes I’ve never heard of – with a refreshing absence of kodak!

The pen and ink drawings of cameras such as the Goerz – Anschutz and the No4 Carbine and incredibly crisp and (presumably) accurate and the page of ‘Al-Vista’ panoramic cameras really did make me want to hand over the required £15 and 15 shillings for the 7×21 model..

The book itself of course is a guide to using all manner of roll film cameras and the technique and clobber needed to get decent results. 13 chapters on cameras, exposure, developing, printing and so on offer the budding amateur masses of easily digestible information, written in a surprisingly light style. If I didn’t know the publication date I would have placed it at least a dozen years later. It has none of the over fussy language that you usually find in publications from the turn of the century – believe me, I’ve tried to enjoy copies of the ‘Strand’ over the years, but barring Conan Doyle and one or two others it can be very hard going!

One thing that did throw me was the seeming mis-numbering of the images – some are consecutive, some not. I finally realised that as the black and white pages are bound in within the printed inners, the images don’t necessarily relate to the chapter that they happen to reside in!

As most of us know Kodak weren’t the only company to push marketing and specifications beyond what’s either achievable or actually required, but the 1/1000 top speed that was available with the Goerz-Anschutz folding camera does get a fair amount of pages – from a show jumper, to a speed cyclist, and my personal favourite the underpants wearing death defying duo performing a faintly homo erotic ‘flying Wallenders’ tribute act – in the vicarage back garden by the looks of things.

The photos vary from pleasant rural scenes, milk maids, haymakers etc to portraits that have clearly moved on from the stern stuff of even ten years earlier – where very long exposures and neck braces would make any sitter look slightly pained.

The illustrations throughout the book show what was available to the keen amateur but one item (on page 22) really caught my eye – it’s a purpose built ‘developing cabinet’ with racks for the chemicals, a plumbed in sink, drying racks and so on – and whether this was commercially available isn’t indicated, but trying to make one today with ‘a shallow lead lined sink..and waste pipe to the drains’ may get you into a spot of bother with the council!

I may not (yet!) have a yearning for a turn of the century stand or hand camera, but I can truly appreciate the fabulously illustrated adverts that are to be found within this guide and at the moment what I do find fascinating are the myriad brands and companies for film, plates, processing and chemicals that are shown – again a very useful ‘snapshot’ of what was available in this period.

I paid £5 for my example of this title – the more usual price (according to ones currently on ABE books listings) would be more like £15. I don’t think even that amount is too much to pay for a visually wonderful relic of what seems now to be a golden period of photography – when most people could have a camera of some sort and the keener ones a hobby that was finally (after 60 odd years) affordable – and relatively safe… lead lined sinks not-withstanding!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

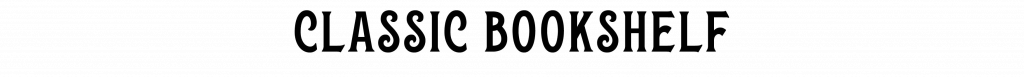

‘The Process Year Book’ 1905-6 Vol XV Penrose’s Pictorial Annual

10″ x 8″

Approx 200 pages plus approx 250 plates and inserts

An illustrated view of the graphic arts

If you have read the title of this book and are wondering what on earth it has to do with photography, the simple answer is ‘lots’!

As a lifelong 2nd hand bookshop browser I have seen countless bound volumes of Victorian & Edwardian periodicals, the common ones being ‘Punch’, ‘the Strand’, ‘Pearsons’, ‘Windsor’ and so on, but seeing this collection in a shop in Todmorden 18 months ago was a first for me. It was a stroke of luck that the shop owner had a whole cabinet of art books and photographic books together, and this one was actually in the wrong section, no doubt misplaced by an earlier browser. I say stroke of luck because I may not have picked it up on title alone.

My day job involves liaising with printers, and I am fully aware of the cost of any printing that involves special processes and inserting of separately printed sheets. This book is basically a year book that allowed printers from all parts to ‘show off’ their skills. I can only imagine that the cost of printing each plate/insert by that particular company was offset by the interest (and therefore orders) that would be generated by potential customers seeing the unbelievable quality that this collection contains. As noted this was an unknown title to me, and given that it is the 15th edition (as in 15th annual collection) presumably this book would be used as a reference by those involved in business that required, for example, a catalogue to be produced, such as a portrait gallery owner, as opposed to someone interested in artistic work. In the latter case the book would be looked after and kept, in the former case they were more likely to bin it after the new edition appeared. As this is NOT a common book this does seem a likely scenario.

Truth be told I actually bought this copy as a birthday present for my father, a man who had a deep interest and knowledge of many forms of illustration, and it was only on having a closer look at the thing on getting home that I realised its importance to a photographica enthusiast.

Firstly a short list of some of the contributors and famous names to be found within the covers:

A feature by Captain Lascelles Davidson name-dropping his good chum Friese Green, articles by Frank m Sutcliffe & Frederick T Corkett, illustrations by Lucy Atwell (she was to achieve acclaim in the 20’s and 30’s), telephoto work praising the Goertz lens, an early discussion of photo criminology, a technical treatise on the Zander process… I could go on!

Amongst the many names, one of the first that caught my eye (as a lover of hammer horror films!) was one that appears on the first fly leaf:

“S.M Frankenstein and Co” – apparently relocated from deepest Ingolstadt to finsbury, London!

As anyone who has visited a gallery showing original hand printed top quality photographs will know, seeing a book reproduction is usually very poor in comparison, but the quality on display here is utterly astonishing, whether it is studio portraiture, rural landscapes, seascapes or architectural interiors and exteriors.

The contributors have covered every aspect of fine art to show their skills and there are reproductions of paintings, sketches and line drawings all done to a superb level – one page is a ‘tip in’ printed on very nice embossed cartridge paper of a pencil sketch which i am certain could fool the people at ‘Antiques Roadshow’ as being an original if it were to be cut out and mounted.

Interestingly there are some contributors who sell not on the quality but by featuring the machinery itself – I can imagine Fred Dibnah going into ecstacies over the illustrations of the ‘Midget and Mastodon’ proof presses- Victorian heavyweight engineering at its best!

Having poked fun at people who look at machinery, I now point the finger inwards as I was excited to see the adverts for Thornton Pickard (imperial & special ruby), Cooke, Ross & Goerz lenses!

This book is a treasure trove of factual company information; as the intention was to gain work, all details are given, something not always the case with ads that ran in the general photographic press. I was familiar with the work by Sutcliffe, and although I thought his images very arresting from a ‘how we used to live’ angle, I felt they look a bit stilted and over considered. Having read his article contained here, ‘Cheap Pictures’, it appears that he was a totally miserable ‘artist’ who disliked the idea that anybody could take a snap, and that the newspapers of the day would sooner pay tuppence for novelty over pounds for quality! As a footnote even Sutcliffe’s address is given in the list of contact details – I wonder if flocks of day-trippers with box brownies went to Skinner Street in Whitby to blow raspberries at him!

The accurate company details mentioned mean that this series is a very important one from a researchers point of view, and although it primarily covers the business end of work rather than the hobbyist, I am certain that it could provide many missing links between companies, working addresses and mergers, details which often leave histories on photographic companies with holes that can not be filled by trawling through the ‘regular’ photo journals.

The vast number of illustrations and special pages do reveal some surprising facts – having noted already that Lucy Atwell is featured in a charming, typically comic colour scene, another very early appearance is that of the term ‘art decorative’ – most would assume that it was coined in about 1925, but it is here used as a title to a beautiful framed painting of an ethereal looking lady in a woodland scene – it is certainly NOT art nouveau, and clearly the next major art phase was already starting to blossom.

So if the cold hard facts of process houses and their equipment are not for you, the beauty and art contained within make the Penrose annual a vital and rewarding addition to the classic bookshelf.

Timothy Campbell (2453)

‘Photography with roll films’ – the Primus Handbook

1903 – the Country Press, Bradford

7×5″ – Hardback

196 pages, plus adverts & inserts

Although a truly life long lover of 2nd hand books and bookshops (I started browsing at the age of 8), it’s only recently that I’ve allowed my collecting to creep earlier than the 1950’s – for me the ‘year zero’ (or technically speaking ‘decade zero’) of all that is photographically inspiring and thrilling – both visually and gear-wise.

There’s something wondrous in spotting a book spine on a shelf that makes all thought go out of your head, that makes the other titles fade away and that connects directly with you – as if it has been sat there waiting for you to pick it up – and leaves you unable to walk away without it.

This particular title I purchased at the rather posh antiquarian book fair that’s held at York racecourse – and it’s possibly the only sensibly priced book that was for sale. It was nice to see a first edition of Cartier Bresson’s ‘The Decisive Moment’ (French language edition – so not actually titled ‘The Decisive Moment’!) but in tatters, pages falling out – for only £750?

The spine of my book is quite faded so it’s quite lucky that I managed to make out the very period type face and titling, but as soon as I saw the cover illustration I knew I had to have it – a more ‘art nouveau’ lady I’ve yet to see!

Most collectors know the value in having either magazines or year books for getting exact info on the availability and specs for certain cameras and kit – the Primus Handbook is no exception. It’s front and end pages are literally jammed full of lists and illustrations of all manner of gear and (for me) most interestingly for film and processes I’ve never heard of – with a refreshing absence of kodak!

The pen and ink drawings of cameras such as the Goerz – Anschutz and the No4 Carbine and incredibly crisp and (presumably) accurate and the page of ‘Al-Vista’ panoramic cameras really did make me want to hand over the required £15 and 15 shillings for the 7×21 model..

The book itself of course is a guide to using all manner of roll film cameras and the technique and clobber needed to get decent results. 13 chapters on cameras, exposure, developing, printing and so on offer the budding amateur masses of easily digestible information, written in a surprisingly light style. If I didn’t know the publication date I would have placed it at least a dozen years later. It has none of the over fussy language that you usually find in publications from the turn of the century – believe me, I’ve tried to enjoy copies of the ‘Strand’ over the years, but barring Conan Doyle and one or two others it can be very hard going!

One thing that did throw me was the seeming mis-numbering of the images – some are consecutive, some not. I finally realised that as the black and white pages are bound in within the printed inners, the images don’t necessarily relate to the chapter that they happen to reside in!

As most of us know Kodak weren’t the only company to push marketing and specifications beyond what’s either achievable or actually required, but the 1/1000 top speed that was available with the Goerz-Anschutz folding camera does get a fair amount of pages – from a show jumper, to a speed cyclist, and my personal favourite the underpants wearing death defying duo performing a faintly homo erotic ‘flying Wallenders’ tribute act – in the vicarage back garden by the looks of things.

The photos vary from pleasant rural scenes, milk maids, haymakers etc to portraits that have clearly moved on from the stern stuff of even ten years earlier – where very long exposures and neck braces would make any sitter look slightly pained.

The illustrations throughout the book show what was available to the keen amateur but one item (on page 22) really caught my eye – it’s a purpose built ‘developing cabinet’ with racks for the chemicals, a plumbed in sink, drying racks and so on – and whether this was commercially available isn’t indicated, but trying to make one today with ‘a shallow lead lined sink..and waste pipe to the drains’ may get you into a spot of bother with the council!

I may not (yet!) have a yearning for a turn of the century stand or hand camera, but I can truly appreciate the fabulously illustrated adverts that are to be found within this guide and at the moment what I do find fascinating are the myriad brands and companies for film, plates, processing and chemicals that are shown – again a very useful ‘snapshot’ of what was available in this period.

I paid £5 for my example of this title – the more usual price (according to ones currently on ABE books listings) would be more like £15. I don’t think even that amount is too much to pay for a visually wonderful relic of what seems now to be a golden period of photography – when most people could have a camera of some sort and the keener ones a hobby that was finally (after 60 odd years) affordable – and relatively safe… lead lined sinks not-withstanding!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

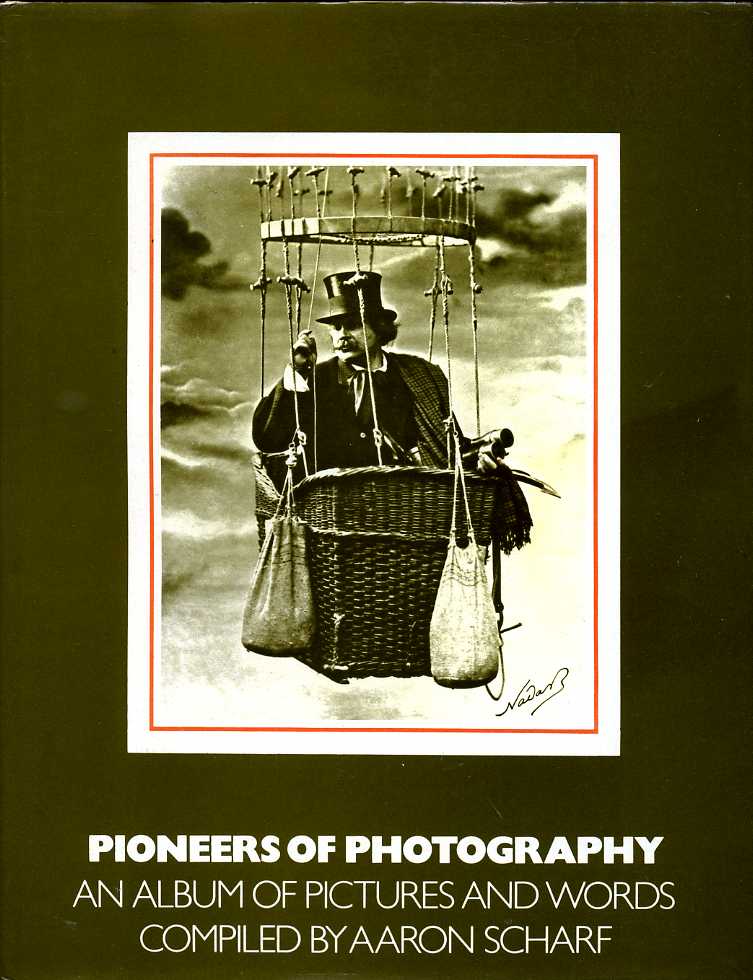

Pioneers of Photography an album of pictures and words

by Aaron Scharf

1975, BBC Books

hardback, 10″ x 8″ 170 pages

I would love to be able to review the BBC TV series that this book was derived from, but sadly (as is often the case with the BBC) there’s no direct source of the programmes – unless any PCCGB member had a video recorder in 1975?!

I say sadly because the contents of this book are utterly riveting, and show a period attitude to photography that is free from bias, free from opinion based on value (the cameras are discussed but purely from a function/development angle, the images are solely viewed on artistic merit) and there’s a refreshing tone throughout that is informed and engaging without being too bogged down in the subject matter, or historic importance of the people and images that they produced.

It is often the case when researching any topic from history (however recent or distant) that one comes across the same quotes, and often the same lazy repetition of info that ultimately becomes ‘the facts’ – this splendidly illustrated book avoids this scenario by presenting each chapter/subject matter with a few paragraphs detailing their place in the chronology of photography, the obstacles that they were trying to overcome, then quoting (mostly unedited) whole sections of period letters/reports/writings from the photographer in question – these are dated and cross referenced with appropriate images to give an incredibly vivid and truthful picture of the pioneer’s particular role in the grand scheme of things – ‘truthful’ is possibly not the correct word, for even the most humble of persons is likely to either exaggerate the success or failure of their work (depending on whether you are the slightly timid Fox Talbot or the full blown showman Nadar), but this is as accurate an account as you are likely to get on the matter.

That ‘truthfulness’ struck me when reading the chapter on Julia Margaret Cameron – when studying her work at college, I found her sloppy technique and posed re-enactments of characters from history all a bit “amateur dramatics” in their style, but reading her breezy accounts of working with collodion made me look again and see past the slightly messy surface and realise that she was in fact far more accomplished than I’d originally thought – possibly you need to be more than 22 years old to appreciate the subject at hand (as I was when studying at college)!

A very interesting account is in that chapter on Cameron, and again shows how you cannot take people at their word – the writer details (quite humorously) on sitting for JMC, and goes to great length to express the agony of trying to sit motionless for a 4 minute exposure while balancing a wayward tiara – now this may seem to be nit picking, but the exposure even on collodion and a very slow lens would be nowhere near 4 minutes, and yet how many people will have assumed that to be a true reflection on the exposure times of the day?

The splendid introduction to the book gives a brief pre history leading to the announcement of photography, including the vital work done in the few decades leading up to 1839, and also covers the camera obscura and the camera lucida, and the way that those same bits of apparatus were resold to the public with assorted names and exaggerated claims (is nothing new?!) – although who could resist a product called the “Universal Parallel”!

The ten chapters cover Fox Talbot (with the full introduction to ‘The Pencil of Nature’ reproduced, which is fascinating to read), Dageurre and Nadar, through the remarkable work of Samuel Bourne, the motion experiments of Muybridge, the artistic endeavours of Stieglitz and Co, finishing with a round up of colour work up to the Autochrome.

Each chapter has many wonderful images, a number of which were reproduced for the first time in this book in an attempt to provide a more broad view of what was being produced during the first 70 odd years, and to show that far from being a rigid, constrained (by the limitations of the technology) period, this was a time of incredible vision from a great many photographers – an Autochrome on the 2nd to last page by J C Warburg shows a cow on the beach at Saltburn; that image could have been used on a Pink Floyd album cover in the 70’s and would have been acclaimed as utterly contemporary!

This book is fairly common (and also had a US edition) – I paid £4 for mine just a few weeks ago, a typical ABE guide price is more like £10, but it’s is money well spent – if a picture is worth a thousand words, then what’s a picture AND a thousand words worth?!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

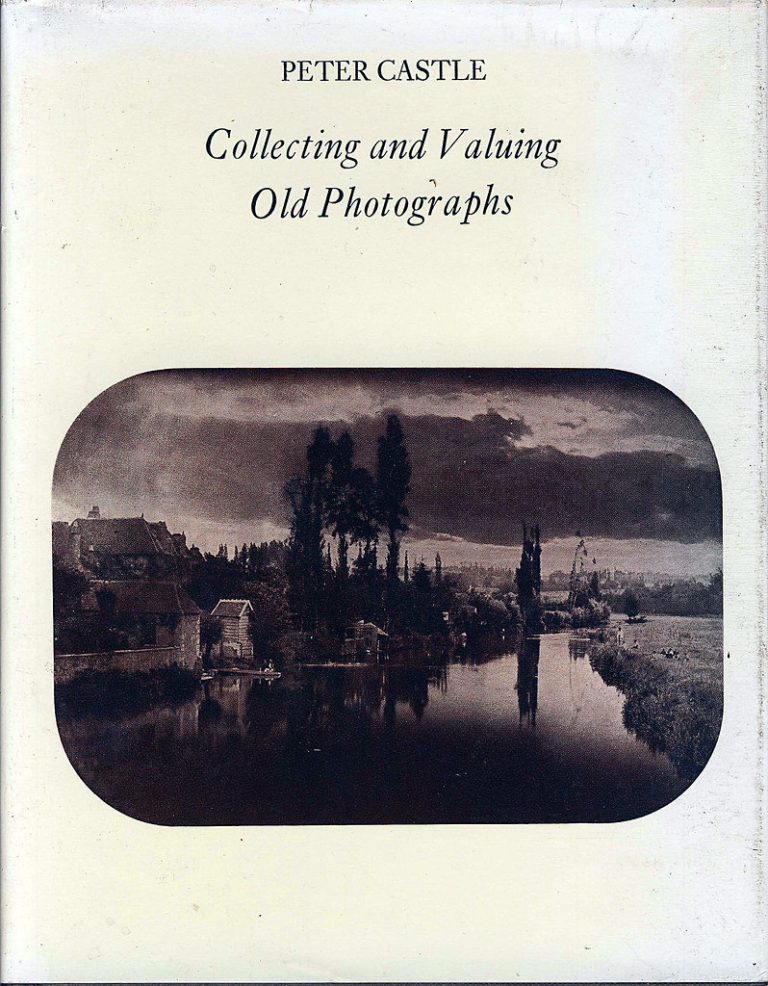

Collecting and valuing old photographs

Peter Castle Garnstone press,

1973

178 pages hardback 6″ x 8″

One of the main reasons for doing the reviews of classic bookshelf was to note how attitudes have changed towards photographica, photographs & cameras in general over the years. This particular book is very interesting example as although it’s a relatively recent, it was written at a time when photography or rather photographs themselves were only just starting to be seriously considered as works that were worth collecting. The main auction houses had started doing specialized sales of the more famous photographers broadly interesting collections of photographs and the various ephemera associated with the very early days of photography. The book offers rough guidelines to the value of period photographs, and also has some actual realized prices from auctions at that time – I’m sure I’m not the only person who does have an interest in the monetary value of such work so seeing how those values have gone up and quite possibly gone down over the years is something which can be of interest even if we don’t have any of these items in our collection. Personally I don’t have any photographs in my collection (other than those I’ve taken myself of course).

Peter Castle at the time of the publication was in charge of the photographic collection of the Victorian Albert Museum, so was in a very good position to be able to produce this book.

The book itself basically consists of six chapters covering such topics as history, famous photographers, famous firms, unknown photographers, how to date & value photographs, collecting and preserving and so on. There is also very good appendix of photographic collections from around the world, and also a very very interesting and quite thorough reading list.

It is incredibly frustrating now to read a book that contains suggestions of items that may be of worth collecting – in 2016 there’s absolutely no chance of buying many of the items under discussion here unless you happen to either win the lottery or you inherit a collection from a relative!

The book itself is nicely illustrated, has very good layouts and thankfully good reproductions of the photographs involved. They are black and white only but then of course the photographs themselves were in black and white, although strictly speaking, sepia.

My example does still have the dust jacket, and the cover shot is a sepia tinted photo by Camille Silvy of a beautiful river scene, and although the sepia toning was a necessary part of the production of that particular photograph, It really does add to the the beauty of it. The image itself is reproduced in the book in black and white and really is no comparison. One wonders how wonderful the original must be to look at…. It’s a shame that the accessories and ephemera which are featured such as stereo viewers, union cases and so on haven’t been reproduced in colour, but at the same time, you do have to bear in mind that it’s only recently that full colour illustrations in books has become commonplace and the cost of producing those colour pages has dropped dramatically.

The only downside of this book is that overall it is really quite poorly written with far too much repetition, even on the same page. I would have liked a simple tabular ‘ready reckoner’ for calculating values, and removal of the much repeated fact that a photograph by known photographer will be worth more than one by an unknown photographer, and that a photograph of an interesting subject will be more valuable than a photograph of a boring subject.

As mentioned earlier a purpose of classic bookshelf reviews are really to indicate how attitudes have changed towards photographica over the years -and that also includes the photographers themselves. More recently photographers such as Lewis Carroll and Edweard Muybridge, although important in their own in their own time have under scrutiny as being slightly suspect. Although you could argue that Muybridge having nude models in his locomotion images is a great way of illustrating how the human body works under certain actions, whether that he needed to be quite so thorough and have everybody starkers is open to to debate, but the more serious shift in attitude is towards Lewis Carroll, who more often than not these days is regarded as slightly suspect with regards his subject matter and the poses of his sitters. While absolutely not obscene, it is true that quite often people feel quite uncomfortable when discussing his photographs these days. And yet at this time (1973) the short biographic paragraph on Lewis Carroll contains “Carroll was always at his best with children, and this is perhaps why his pictures of little girls – Carol did not like boys – are among the most charming examples of child photography in the Victorian era”. Many people would no longer use the word charming in discussing his images, but maybe that’s just the attitude of today – in 10 years time it might have changed again!

Valuations given in this book are very, very general although it does very helpfully give actual achieved prices. It’s quite incredible to read that in 1971 a copy of Fox Talbots “the pencil of nature” sold for £2100 – and that was an incomplete example! I’m not aware of that most famous book being listed recently in the Tailboard auction (but you never know). What’s it worth now? Priceless, really.

Julia Margaret Cameron and Lewis Carroll individual photographs in 1973 would be expected to fetch £230 plus Hill & Adamson original photographs at the time £700 plus, so I assume that in the early 70’s it was possible to buy these things…

I picked up this book in a shop bookshop in Todmorden in late 2015 for £3 and it’s in excellent condition, there’s plenty of copies in ABE books from that price – in summary, this book is well worth having, It is a very good period piece, and while not an academic book or even particularly thrilling reading, as a reference it is an excellent starting point to the world of early photographs and makes a very nice addition to the classic bookshelf.

Timothy Campbell (2453)

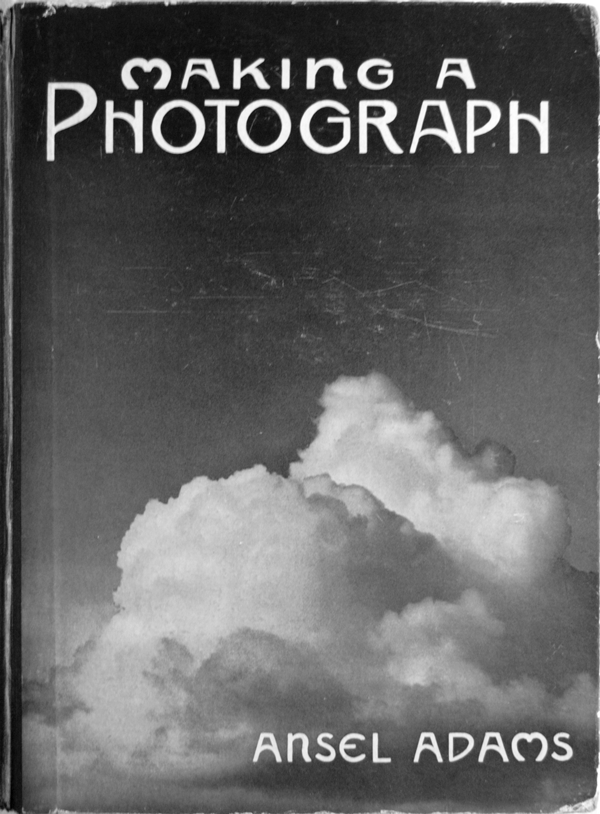

‘Making a photograph’ introduction to photography by Ansel Adams

(from the “how to do it” series number eight)

Published by the studio limited 1935.

Hardback – Quarto size 96 pages, 25 black and white photo plates.

I find it interesting that this book is called making a photograph as opposed to taking a photograph, but that title in fact is the perfect one because Ansel Adams approach to photography is very much to do with making it, not merely taking a record of what is in front of the photographer/camera.

Readers will no doubt be familiar with the many classic images that Adams produced, particularly the ones from Yosemite National Park and also his approach to the ZONE system of both taking photographs and printing photographs to maximise contrast and detail across the entire black and white spectrum.

This book is interesting in so many ways and his style is encouraging, engaging and entirely easy to grasp – given the complexities of the subject this is quite an achievement. It’s a book which I wish I’d become familiar with when I first started in photography – as opposed to 30 years later!

I came across this book in a second-hand bookshop in York, with a typical York price tag(!) but I was allowed to have a thorough browse through, and to make a note of the details. What struck me was firstly the very much of its period type face that’s used on the front cover, but also what I found fascinating was that the black-and-white illustrations are actually tipped in i.e. hand applied to each page – after 70 years some of that glue has dried up giving it the impression of being a hand assembled photograph album. I’m sure that in 1935 the pages the images would have been stuck firmly, but in fact that hand assembled look makes it very appealing. I mentioned seeing the book to editor John marriage, who it turned out has a copy of the book, and that’s what I’m now reviewing.

I was a bit confused to read that ‘making a photograph’ is from “how to do it ” series number eight and initially I thought there were seven books before this one by Ansel Adams, but in fact the series covers many different areas of the arts, by different experts in their respective fields from making an etching, to wood engraving and woodcuts, making a watercolour, sculptor, portraiture, pottery and potting and so on.

By 1935 photography was was no longer the preserve of the extremely wealthy – it was available to just about everybody from the most simple snapshot approach of the typical Kodak user, all the way up to large format photographers and photographers in the field, the area where Adams would have of course make his name.

The simplicity and very methodical approach that Adams uses is in complete contrast to the introduction by his friend Edward Weston, and I quote “the chemical mechanical nature of photography precludes all manual interference with its essential qualities and indicates a fully integrated cognizance of the aesthetic problem under consideration before exposure. The conception must be seen and felt on the camera groundglass, complete in every detail. All values, textures, exact dimensions are to be fully and finally considered – for with the shutters release the isolated image becomes unalterably fixed, developing the negative and making the final print completes the original conception”… If that isn’t enough to put anybody off photography or discussion of photography. I don’t know what will!

Contrast that with Adams own words (on aesthetic considerations) “Photography is distinct from the other graphic media in that it is analytic in its approach and rendering, while painting for instance, may be analytic in approach, but synthetic in rendering. The painter can organise his subject elements within a given space. The photographer must organise a space for his subject elements”.

This is clear, concise and pared back to the most fundamental principles.

The book contains chapters on choosing a camera, materials, theory, making the photograph and types of photography.

This really is a splendid book, beautifully illustrated, very easy to read and I feel is a true landmark in photographic books.

The current price on ABE Books is from £50 – £60 upwards. It’s worth noting that due to the the glue which was used in the tip in process, potentially images could be missing from some the pages – so I’d advise fully checking before handing over your money. Possibly the book may have had a jacket – but none of those listed on ABE mention one.

The other books from the “how to do it” series are in a much more affordable £10-£15 bracket, which is slightly frustrating, but understandable!

Highly recommended.

Timothy Campbell (2453)

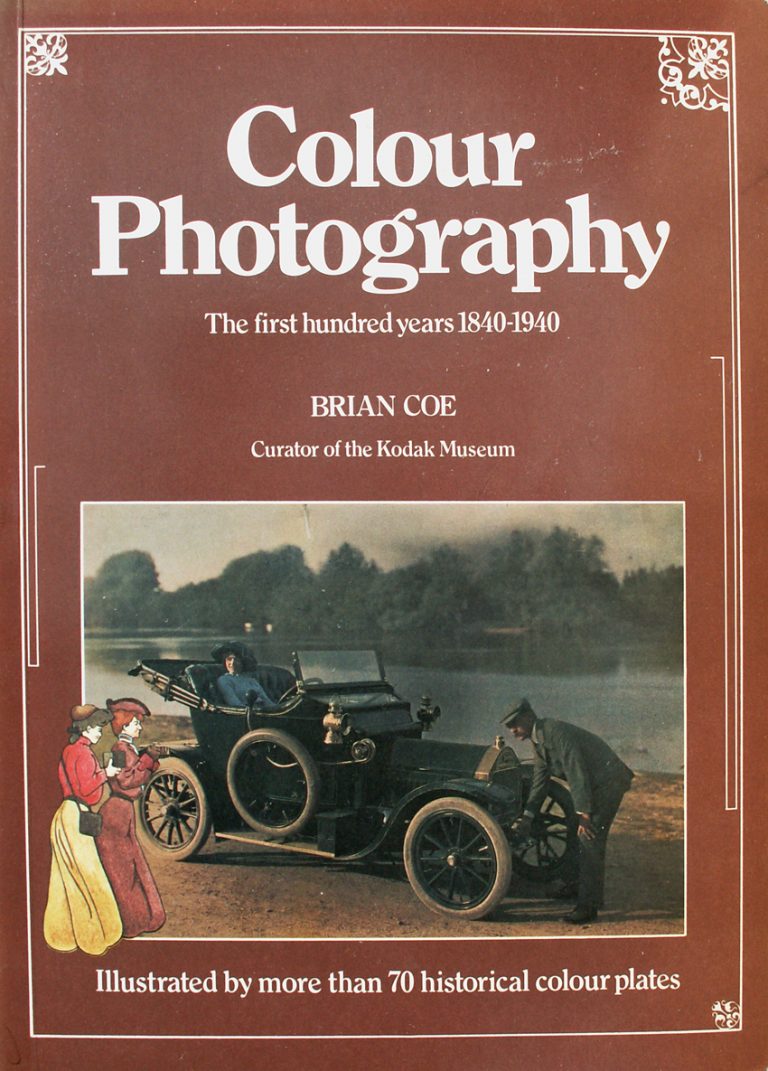

‘Colour Photography – the first 100 years 1840 – 1940’

Brian Coe – Ash & Grant A4, 144pp – 1978

Brian Coe is the author most likely to be known to members of the PCCGB, if not by name then certainly by his books. There cannot be many members bookshelves that haven’t got nestled next to the current edition of McKeowns, that stalwart of collectors tomes ” Cameras – from Dageurrotype to instant pictures’. That book with its superb overview of camera design and development, may well feature in a future Classic Bookshelf review, but this article is on the book that was published in the same year (1978) but is on the more specific subject of colour photography itself. Given that 2007 is the centenary of the first commercially successful colour reproductive process (the Autochrome), and coincidentally the BBC have been running their excellent ‘Edwardians in Colour’ series, and last but not least the National Media Museum, Bradford have just opened their ‘Dawn of Colour’ exhibition, it seems timely to review this book.

As with mr Coes other books, this is extremely readable, no mean feat given the sometimes quite scientific information that he is covering. It is astounding to discover that the methods of colour reproduction actually go back to virtually the beginning of photography itself, although progress was limited not by the lack of understanding of light properties, but rather by the difficulty of producing sensitive materials in the first place, made three times harder by the need for different materials for each of the basic colours required.

The excellent thing about this book is that it is possible to look up information on a particular process without having to read from page 1. There is plenty of cross referencing, so that vital info that relates to multiple processes is basically detailed only once. However, reading the book right through gives the reader a very enjoyable journey through the highs and lows of the various inventors and manufacturers, and how one processes success or failure was picked up on by later companies. The aforementioned Autochrome process, although perfected by Lumieres in 1907, was actually detailed many decades earlier, but not taken through to fruition.

I am a self confessed ‘nut’ for any camera design that is unusual, and there are a multitude of excellent photographs and contemporary adverts for the cameras covered. This unusual aspect is especially true of the early 3 plate cameras, using a single exposure, but beam splitting onto differently sensitive monchrome plates.

There are also line drawings to show the inner path that the light takes with these cameras, and it is fascinating to see this path, complex doesn’t begin to describe it!

Before I got this book, the only pre WW2 colour images I had seen, were the bog standard ‘tinted’ monochrome images that most families have kicking about somewhere. The breathtaking beauty of the Paget plates, Autochrome, etc contained in this publication are a revelation, and really makes this book a ‘must have’. A few more illustrations are also most worthy of note: the first is the photomicrograph of the various emulsions which goes some way to explaining the characteristics of any particular process, for example the Autochrome was actually a layer of three differently coloured potato starch grains (red/orange, green and violet) the gaps between these filled with charcoal dust, resulting in a slightly soft, not quite accurate colour palette, that nonetheless is extraordinary -how on Earth those Lumieres Bros were able to acuurately mix 3000 of the grains per square millimeter is beyond belief!

The second great illustration is of a photo from 1927, taken on Kellar Dorian Berthon film using a Leica with a special filter attachment, that produced a lenticular image – a ‘failed’ process that was eventually taken up in the 1980’s by the Nimslo company – and failed again!

The reason for the 100 year span of the book is that 1940 was the year that Kodachrome was perfected, knocking all other attempts at a useable process into a cocked hat – the full page shot of a pilot in front of his Spitfire is as morale boosting as it is a benchmark for quality, even today. The films may have got faster and less grainy, but the colour accuracy was reached all that time ago. All developments (no pun intended) since then have been just that, not new inventions, even the polaroid process is a variation on a much earlier dye transfer one, but you’ll have to look it up yourself to find out which one!

The knock on effect of having read this book, is that it has given me inspiration to recreate some of these processes digitally. I am happy that I have the skills and experience of black and white processing and printing, but I am surely not the only one who hated the unpleasant conditions that it requires. The one great advantage of the ‘digital revolution’ is that it is so easy to scan even the most unpromising negative, and fiddle with the tonal range to get a useable result. Once you have a decent scan, it is very satisfying to add washes of colour to all or specific areas of the shot, to locally add blur, and so on, without resorting to X rated chemicals in a cramped, humid smelly darkroom. Of course you do need a scanner, a computer, a printer, a copy of Photoshop, and probably a year or two of getting to know how to use it all, but it is worth the effort!

Although the book isn’t currently in print, it is readily available through the usual second hand bookshops and fairs, Ebay and probably easiest of all ABEBOOKS (on the internet). Expect to pay around £10 for the softback, and up to £20 for the hardback.

I urge all readers to track down a copy, and put some COLOUR into your collection!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

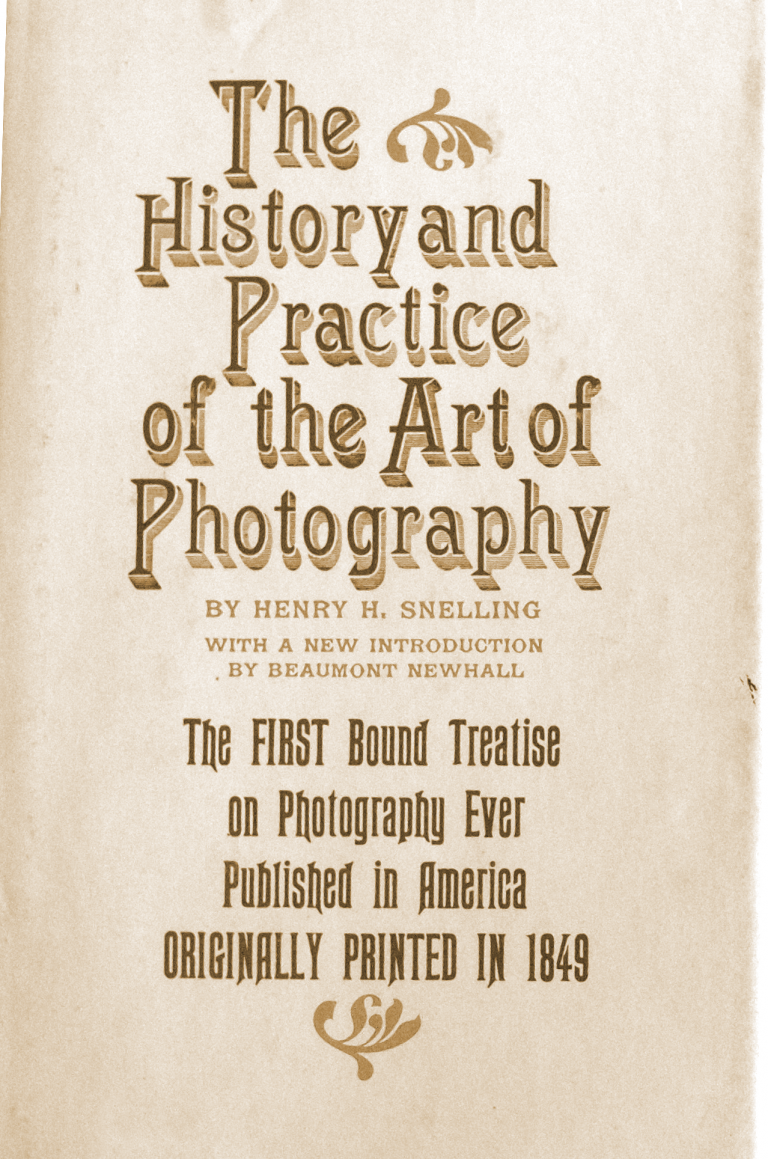

The History and Practice of the Art of Photography

By Henry H Snelling

5″ x 7.5″, Hard cover, 146 pages, Published 1849, Facsimile reprint, Fountain Press 1970

This book was one of those chance buys which happen when you trawl second-hand bookshops – an uninspiring cover, a period of photography that is more than 100 years earlier than my personal preference; I should have left it, but for £4 I decided it might be of passing interest, and as it turns out this is in fact a VERY interesting period piece, full of detail, information and above all an attitude which made for an occasionally disturbing read – and I thought I wasn’t particularly PC!

The blurb on the jacket states “the first bound treatise on photography ever published in America originally printed in 1849” so I think I can be excused for not getting too worked up on first sighting. It’s true that the text is very much of its time, although being by a US author it is far less pompous and wordy than typical mid-Victorian English writings (what’s the American equivalent of mid-Victorian?).

The basic reason for the book’s original publication was to help photographers with a full and detailed explanation of the processes, procedures, formulae and equipment needed to achieve successful results. This may not sound like much but, believe me, as someone who thought they knew what creating either a Daguerreotype or Calotype involved I am now amazed that anyone ever managed to do so – and to think this was 10 years after the birth of photography…

I mentioned earlier that this is an occasionally disturbing read – the author for some reason has clearly ‘got it in’ for Fox Talbot, and generally any English photographer – “English portraits are far below the standard of excellence of those taken by American artists… I have seen portraits that our poorest Daguerreotypists would be ashamed to show to a second person, much less suffer to leave their rooms” – and that’s on page 6! Further reading reveals that Snelling was very much against Talbot’s business of charging a high price to show how to produce a Calotype, whereas Daguerre gave his invention FREE to the public – ignoring that Daguerre was paid a handsome pension by his government for his work.

There are many other flag waving/patriotic rants against the British – best left unmentioned here, as I would like to move on to the positives… There a quite a few very nice illustrations, showing typical cameras and gear – the Voigtländer canon being instantly recognisable, and it’s nice to see the wooden contraptions that were available, or at least made and used by the snappers of the time. Mention is made of a sand powered timer by ‘Constable’ of England – this appears from its description to be a giant wall mounted egg timer affair – I wonder if one still exists?

There are full instructions on virtually every method available at this time, and variations on chemicals, intensifiers, home brews etc which would have been a godsend to the eager dabbler… assuming that attempting to use bromine and fluoric acid didn’t damage either lungs or other vital organs, or the insanity of connecting a battery to the camera plate as outlined by the ‘galvanic method’ – patented by Dr Frankenstein, I presume?!

To say these methods are involved is a massive understatement, and how on earth anyone would have the resolve and patience to mess about with it all is beyond me, but does raise my admiration considerably. There is a passage on exposure times that I’ve never heard of – certainly most photographers of a certain vintage will know that you need to allow for seasonal differences in light levels, but country to country? Apparently that was the case – possibly this is to do with reciprocity failure and recalculation. I found it surprising that in the last few pages of notes (including that one) there is a quote from the London Art Journal of March 1849 regarding Daguerreotype plate sensitivity – although the exposures were then in the seconds to minutes range, a Mr Claudet showed that the plates could in fact be exposed in 0.0001 second! All he needed to do was invent the electronic flashgun!

There are many other amazing possibly-forgotten-about gems in this book, I don’t claim to be familiar with every aspect of photo history, but I have truly had my eyes opened by reading this volume – how to restore faded images, the ‘Crayon” process (possibly mistyped – it’s also mentioned as the Crayton process), colour experiments undertaken by Herschel, Rondini Lunar images… and many more!

As this is a facsimile there are a few typos, most of which are not confusing or misleading but given Snelling’s ‘Hey, Hey USA’ attitude I found it very satisfying to see hubris blasted to atoms on page 105 – he mentions that the Calotype process has been used in printing in England, but ” it possesses no advantages whatever over the method with type, brought so gloriously to perfection” blah blah, there is then a misalignment of the text which does require the reader to turn the page back to work out which bit goes with which! – presumably corrected for the 2nd edition!

This book was produced in USA, but also by UK Fountain Press, it’s easily available via ABE for about £5 – as mentioned the jacket isn’t thrilling (so not worth paying extra for), but they have embossed the cover which is a lovely touch, and bearing in mind that an original will set you back several hundred pounds this really is a bargain!

Highly recommended.

Timothy Campbell (2453)

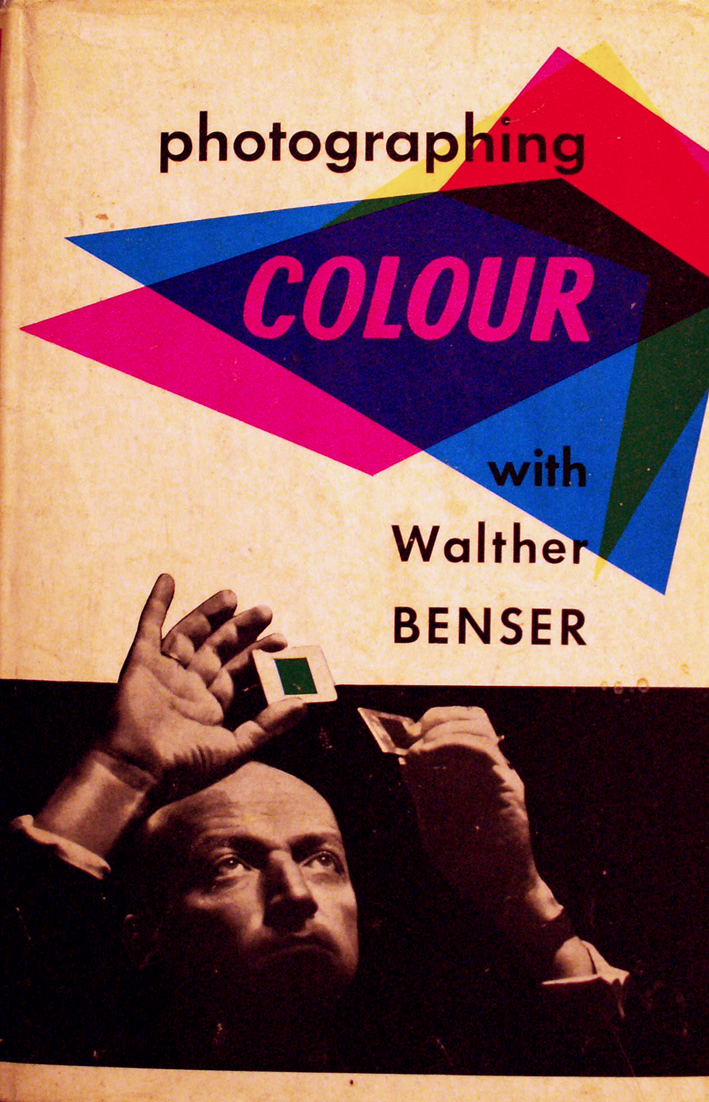

“Photographing Colour with Walter Benser”

Fountain Press, 1961, 202 pages A5

Although this book may not be familiar to many members of the PCCGB, the author should be known to most Leica users, as he was a regular contributor to the flagship publication devoted to that marque, ‘Leica Fotographie”, going right back to its German language (with handy English translation insert) origins in 1952. His regular feature was entitled ‘Marginal notes’, whereby this most genial photographer/writer would ponder on his recent field tests, mostly of Leica equipment (being Leica, he must have struggled to come up with new superlatives year in, year out!), relate stories of his experiences as a globe-trotting – lecture giving pro’, and most importantly of all, give his guidance as to the road to better photography. Given his wonderful success as a lecturer, it’s not surprising that he was able to publish a series of books, from the 1950s onwards, all geared to this common theme – that of producing first class colour photos.

The particular edition under scrutiny is actually an expanded reprint of his first book that was entitled 35mm Colour Magic, published by Fountain in 1956. Why have I chosen the 1961 edition you ask? I’ll tell you why – it’s because Benser’s wife Ursula provided very humorous, but none-the-less informative line drawings for this edition.

What I find fascinating about photography, and in particular photographers, is that the more technology ‘advances’, the more people are willing to believe that this automatically equates to an advance in quality, when in fact the best that automation can do is help everyone get an average result most of time, regardless of experience and/or knowledge. I appreciate that a lot of people are not interested in the physics of photography, but surely everyone who goes to the trouble of taking a photograph does actually want it to look good? Or do they only want average?

The aim of Better Colour Photography is to show all readers that with a little thought all photographs can be improved. Now there are hundreds of books on this subject, but I guarantee that none of them have the easy going, non-preachy accessibility of Mr Benser.

He was aware that people could (and still do) miss out on the pleasure of a well taken, correctly exposed photograph, due to a lack of understanding of the principles of photography. This book was written to encourage the photographer to quickly understand the potential pitfalls of virtually any photographic situation, make allowances, and produce significantly better photos.

Now getting that information across to the novice (or advanced) snapper is a tall order, but a combination of light writing style, wonderful colour plates, and as mentioned earlier, the funny, charming illustrations by Mrs B, all amount to an invaluable, helpful, and most enjoyable book, which NEVER bores with science or rambles with dull text, and makes salient points hit home with total precision.

The author himself, in the brief ‘welcome’ section, explains ‘How to read this book’, and encourages you to dip in and about the book, to the areas that hold the most interest, as he says ‘ you would a tourist guide describing in detail places that you would want to see’ – how many authors invite you to NOT read their work thoroughly? But, trust me, flipping through the pages, you will linger, and thus the cannily couched pearls will appear before you, and almost unconsciously, your photographic know-how will grow!

A few examples of the illustration as tutor approach:

(1) Drunken man on lamppost pic:

At first you think it’s funny, as both drunken man AND photographer are leaning on lamp posts – but then you notice that it’s night time, a ½ second exposure is required – snapper leans on post for steadiness. Result – sharp picture of drunk man!

(2) Sailor with lady at table picture:

The background is too fussy, raise the subject up (or lower yourself): Result – No chimney growing from her head!

And so it goes on.

There is a very thorough contents/index, listing at length the various topics, making this dip in approach easy.

A section devoted to light meters and their usage might seem totally irrelevant in a world of built in convenience, but the techniques of getting correct exposure still apply, possibly even more so nowadays. Nikon, and their ilk, should be congratulated on producing 29 segment matrix metering into their cameras, but when I take a photograph of my wife, I want her skin tone to be perfect, not the surrounding countryside, so using that matrix metering will nicely average everything out into a middle tone, producing on an average day, an average result! By using Benser’s guidelines, I already know that the skin tone is the most important bit, I take a close up reading from that area, transfer that info to the camera manually, take the picture: result: scintillating skin tone, satisfied snapper, satisfied wife!

Walter Benser’s books were all successful, and so are quite readily available, usually in the £5 – £10 range, even with a jacket. I heartily recommend this book, as I believe that even the most experienced photographer can benefit from a refresher course, and this book is certainly refreshing! That it is fifty + years old makes no difference as the info it contains is totally relevant today (which is not always the case).

If you would like a further read, Walter Benser also published his autobiography in 1990, titled “My Life With Leica” (Hove Books), although probably due to having the magic word Leica in the title, this tends to be a bit more expensive (up to £20 or so), but it is a fascinating eye witness account of the early days at Leitz, scary Second World War experiences (told from the German point of view), and thrilling stories of his lecturing escapades in lands that at that time were not used to seeing cameras and foreigners!

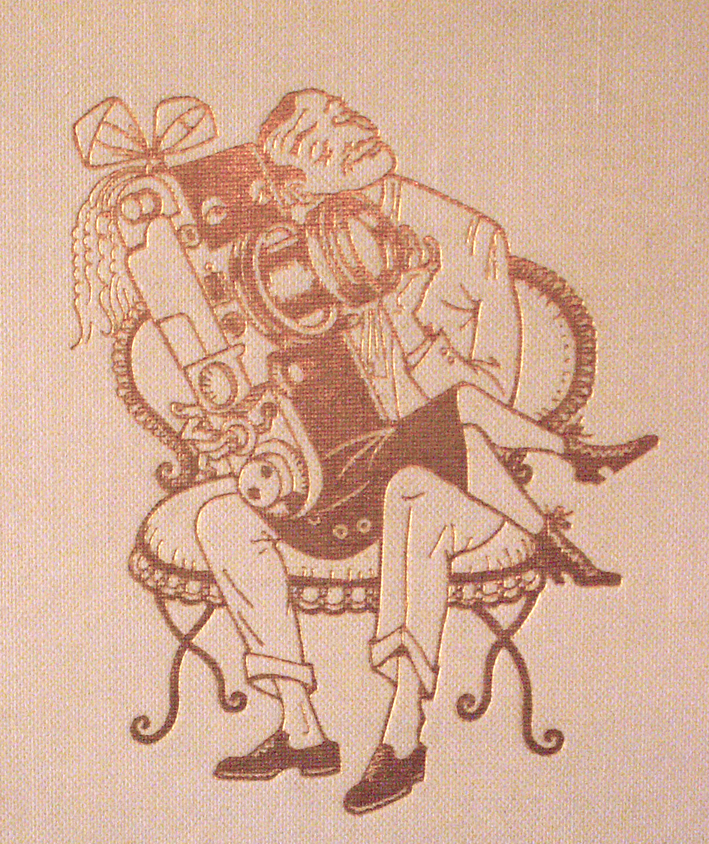

A final note on my copy: I had had the book a little while, and realised that the cover was in danger of getting tatty, so I decided to remove it to give it an acetate wrap: I then saw for the first time, the wonderful gold blocked cover illustration showing Walter cradling his ideal ‘woman’ – a Leica camera with arms and legs!

Clearly he had a very understanding wife!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

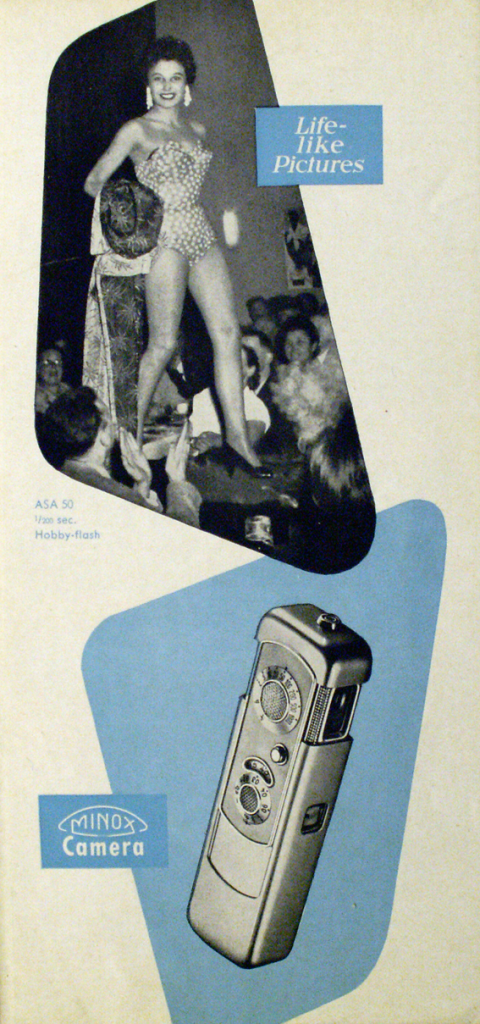

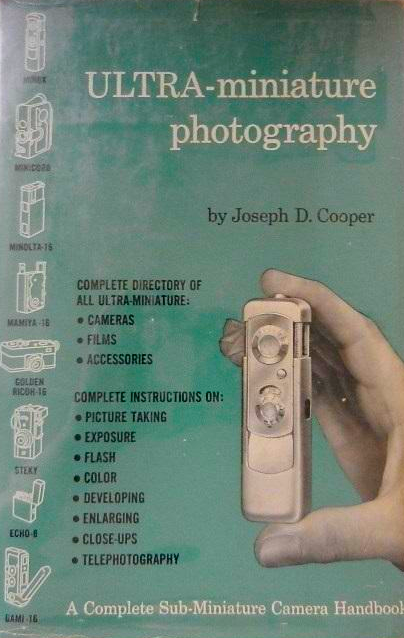

Ultra Miniature Photography, by Joseph Cooper

Universal Photo Books, New York 1958

“This is a book about Ultra Miniature cameras and their accessories; it will help you choose equipment, take good pictures, and get good prints”

This is the opening sentence to the preface of this most wonderful book, a book which is not only engagingly written, but is a true ‘snapshot’ of the period in which it was written. The author successfully puts across the necessary information in a very easy to digest manner, and achieves that rare distinction of not bamboozling photographic newcomers, while teaching old dogs new tricks.

If you think you’ve got good photo technique, try taking (and processing and printing) a decent shot with a subminiature camera! Camera shake doesn’t only occur with a big heavy camera, you know!

The chapters cover all the usual photographic elements, from selecting a camera, how to expose, develop, print, using accessories, and so on. What makes this book unique (at least in my experience) is that Cooper not only illustrates the book with GENUINE sub-miniature photos, stating the camera type, the film and the developer used, but shows (in many cases) the original negative (reverse printed) next to the ‘blow-up’ – if you’ve never seen an actual size 8x11mm Minox frame, and the achievable result, be prepared to gasp in disbelief!

This camera/print comparison is invaluable to a sub min nut, such as myself, as it’s possible to at least see the legendary quality of the Italian Gami 16, even if I can’t afford to buy one – assuming I could find one, that is! That there is a close up attachment shown in the accessories section makes you wonder if that was the only one in existence…

On the subject of values, Joseph cooper thoughtfully gave current list prices, in US $, for each of the cameras then available, all used to illustrate the book – these are, at a 50+ year distance, very interesting: The aforementioned GAMI 16 was then $297.00 (now perhaps $1000), the German Cambinox $399 (today $1200), The Minox III-s, Minolta 16, Mamiya 16 are currently the same value ($150, $35, $39), but the shock is the Camera Lite, currently $800, then less than $10.

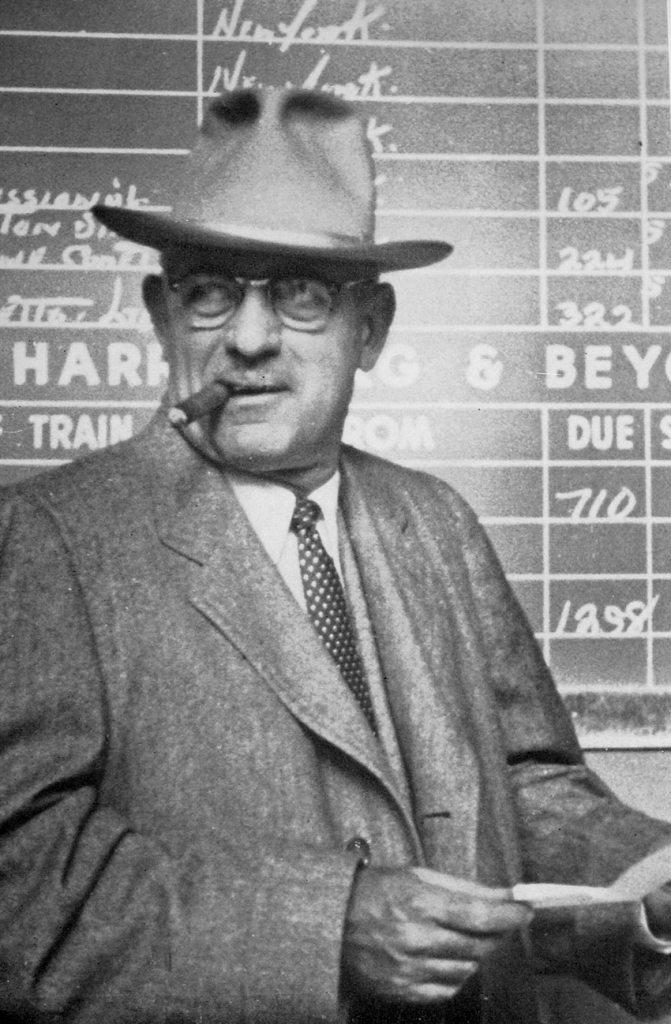

One of the photos shows a camera shop window with a display of discounted HIT type cameras with a card saying 52 cents! This period aspect is of course reflected in the photos used, and incidentally what makes books (and magazines) from earlier times such an interesting thing – apart from being very affordable! A sample of illustrations shows a New York street scene, complete with vehicles to make a car lover lick his lips, various photos of men looking like FBI agents (did everyone wear hats, then?), and women who have actually got their tummies covered up. And did I mention smoking?

After a quick trudge through the Internet, I found that Mr. Cooper did a follow up in 1961, which includes the Swiss Tessina, and the then new kids on the block, half-frame cameras. Certainly one to add to my collection, I think. The beauty of the web, and especially eBay, is being able to get at least a rough guide to the SELLING price of things – valuing cameras is fairly easy, but books? It’s a minefield. For instance I found two Minox specialists listing the book (the Minox does feature quite heavily in it) for $80, and £75, and yet on eBay it usually goes for between $15 and $20, and if it has its jacket it’s a bonus.

Talking of bonuses, when my copy arrived from the USA, the previous owner left within its pages a very nice bookmark – a late ’50s Minox IIIs info leaflet, now (possibly) worth more than the book itself…

I hope this article has stimulated you to check out dealer’s dusty shelves, charity shops, and of course, eBay for your own copy of Ultra Miniature Photography – it’s a black and white marvel!

Timothy Campbell (2453)

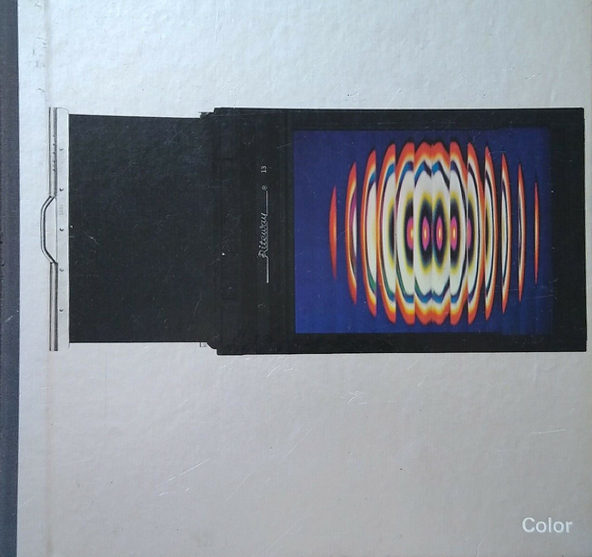

Time-Life Library of Photography

17 volumes, 1970, 236 pages each, hardcover(s)

I am certain that virtually every PCCGB reader will have seen, if not actually own at least one of the 17 volumes in this fabulous series. They stand out a mile due to the almost minimalist design with striking silver covers, and 10″ square size. The earliest copyright date appears to be 1970, but some of the volumes I have are later in the 70s, although I’ve not been able to check if the later books update info from earlier editions. In a nutshell, the titles cover cameras, the studio, photographing nature, the great photographers and so on. Each of these volumes offer a wealth of technical and visual info on the particular subject, delivered in a no-nonsense fashion. They are a mix of B&W and colour, and as a Time-Life publication, the quality is superb – the paper stock being quite heavy high gloss. The technical aspect of photography is of course still totally relevant, and the use of then contemporary work is very inspiring: Seeing William Eccleston’s images of the more mundane parts of America all shot in remarkable colour tones is fantastic, and that he was trumpeted then (in the USA) makes it more surprising that it’s only recently that he was appreciated in the UK. There are many more photographers and visual styles that are well worth exploring, and many are featured in more than one title, from a different viewpoint: it is here that the (now) difficult to find separate index comes into its own. I was originally given ‘The Camera’ as a present, and over the next few years picked up odd titles during visits to secondhand bookshops, and scored a bullseye when I was offered a box full of photography books from a book dealer friend containing virtually all the remainder. There is one title which is very rarely found, and I was told by a specialist photo book dealer that they once got very unpleasant attention for stocking ‘Photographing Children’ – a sign of the times, sadly.

Time-Life also produced a photography yearbook during the 70s (and possibly beyond), and these are also very interesting to the modern collector. They have sections on the main American exhibitions for that year, the marketplace, new books, and equipment development – not all of which came to full production.

The series were produced for at least 8 years, and are readily available (with the exceptions already noted), they are usually under £5 a book (and often cheaper) and as a set make a very handsome two foot wide addition to any bookcase. Given that they contain articles and information covering the start to the (then) present day, they are an invaluable time-capsule insight into the American opinion of all things photographic.

Timothy Campbell (2453)